Economics of Poultry Feeding: From least cost to maximum profit feed formulation

We often forget (or forget to teach) that the mathematical program known as linear programming, often known as "least cost", when in actuality it can be used to determine either least cost or maximum profit. One of the problems that the author I think overlooks is that for many nutrients feeding less than a requirement can lead to disastrous results, especially when it deals with trace mineral, vitamins or even amino acids and, feeding in excess of these requirements does not necessarily mean they will gain faster. In my experience over the years, the best profit is obtained by looking at feed cost per unit of gain, which is usually determined primarily by selection of the dietary energy level. In this case, formulating for best cost per balanced calorie is by far the most economical practical means of formulation. It would be nice if we had a lot of the response curves for different nutrients but unfortunately not many exist.

Park W. Waldroup Overall I agree with you. However, the US has been traditionally the largest producer of corn and soybean and the leading chicken exporter. Under those conditions, we obtain the best profit by just looking at feed cost per unit of gain.

To make it clear, in my experience, the best cost per gain is obtained by formulating for least cost per balanced calorie. This has been demonstrated a number of times in scientific literature and my experience in formulating diets for some of the leading broiler and turkey producers have borne this out. If you want to see it in action look at the drastic drop in dietary energy levels (and levels of added fat) from 20 yrs ago to today. It was difficult at first to get this concept across (and still often is) because FCR was the ”golden standard” for performance. Today, the leading reporting services no longer even hint at FCR. A calorie from fat is much more expensive than a calorie from corn. For corn-soy type diets, I add about 1.5 % for physical properties and essential fatty acids.

Park W. Waldroup a couple of question from a young animal nutritionist!

1. I agree that considering FCR in economical decision is outdated. Therefore, we need to add product price in our economical decision regarding feed formulation. Right?

2. I was a bit confused when you said "least cost formulation per balanced calorie". What do you mean by "balanced calorie"? Do you mean keeping a standard ration between ME and other nutrients/minerals?

3. Based on the second part of your speech on reducing dietary fat %, I assume you are choosing a lower ME (lower than industry recommended) but I am having hard time to understand how I can choose a lower optimal ME! What would be dietary ME for a finisher broiler diet where only 1.5% fat has been added? Then are you reducing other nutrients content in a ratio to ME?

I would appreciate your response.

Park W. Waldroup Dr. Waldroup, this discussion has been in the industry for decades, and you have actively participated with a lot of data over the years. So, I think that a little bit of history and actual data may help to illustrate, or better, illustrate again what you have done in reference to formulating to the least cost per balance calorie. At the 1995 Maryland Nutrition Conference (yes, 1995!) Waldroup et al. presented "Growing the large male broiler for further processing - dietary energy considerations".

It was the report of two trials that were conducted with male Ross (presumably 308) broilers which were randomly assigned to litter-floor pens with 50 birds per pen (4.65 sq-m or about 1 bird per sq-ft). Diets were formulated for starter (0 to 21 days), grower (21 to 42 days), and finisher (42 to 63 days) periods. All diets were formulated to meet the nutrient requirements for male broilers suggested by Thomas et al. [1992. Proceedings Maryland Nutrition Conference, University of Maryland, pages 45-53] with minimum amino acid requirements at 105% of the suggested levels. All diets contained 5% poultry by-product meal as a source of animal protein and were fortified with complete vitamin and trace mineral premixes, salinomycin (66 mg/kg) and bacitracin methylene disalicylate (55 mg/kg).

Ten diets were formulated within each period. These diets were obtained by increasing the amount of poultry oil from 0 to 9% in increments of 1% and formulating for optimum nutrient density (energy and associated nutrients). Starter diets ranged from 2985 ME kcal/kg (1357 kcal/lb) to 3333 ME kcal/kg (1515 kcal/lb); grower diets 3027 (1376) to 3379 (1536); and finisher diets ranged from 3078 (1399) to 3436 (1562). Calorie:protein ratios remained relatively constant across all diets within each age period. All diets were pelleted; starter diets were fed as crumbles. Body weights and feed intake were determined at 21, 42, 49, 56, and 63 days of age. At 63 days of age, sample birds were processed in a pilot plant to determine the influence of dietary treatments on processing characteristics and breast meal yields.

At the time of this publication, I was formulating for some of the poultry operations of the Continental Grain Company among them one in Puerto Rico. And by coincidence, I was very intrigued about the subject of this discussion: what was, based on bird performance, the lowest cost formulation? Since the paper by Waldroup et al. (1995) coincided very well with what I was trying to understand I decided to first, contact Dr. Waldroup to get the details of their protocol which was immediately kindly provided by fax, and second, I just replicated the paper's formulation in CGC's least-cost formulation program using the prices at that time in Puerto Rico for the ingredients used by Waldroup which of course were corn-soy, poultry by-product meal etc., quite closed to our formulation reality at the time.

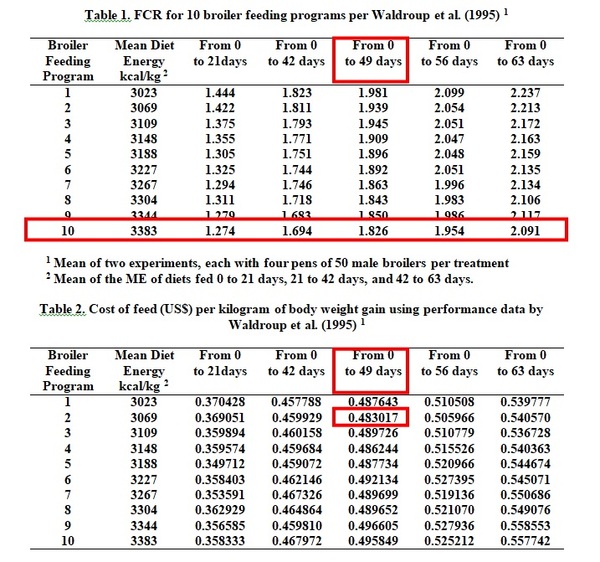

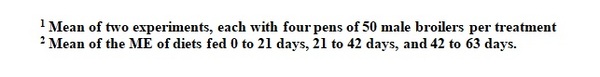

The results and discussion presented by Waldroup et al. (1995) were targeted at live and further processed performance at 63 days of age while my specific objective was to estimate, using their data, the lowest formulation cost at 49 days which was my market. In other words, I wanted to estimate the range of metabolizable energy for the lowest cost of live performance at 49 days of age. As indicated above, overall 10 feeding programs were evaluated for which the Mean Diet Energy (MDE, kcal/kg) were calculated and performance data were reported at 21, 42, 49, 56 and 63 days of age. My final report contained nine tables, however, here for the purpose of this discussion two tables are sufficient.

Table 1 taken directly from Waldroup et al. (1995) shows that with all feeding programs the highest MDE resulted in the lowest feed conversion ratio (only a slight numerical exception at 42 days). However, at 49 days of age the lowest cost of feed per kg of gain (Table 2) was feeding program 2 with a MDE of 3069 kcal/kg and FCR 1.934 instead of feeding program 10 with a FCR of 1.826 for a MDE of 3383. The former is the optimal lower cost of ME for this dataset at 49 days of age. Table 2 also shows that there are relatively minimum differences around programs 1 to 4, which were low ME with low levels of added poultry oil. However, at much higher levels of added poultry oil (therefore higher MDE) the cost difference is economically significant. Program 2 versus Program 10 at 49 days of age for 1 million kg of broiler meat is $12,832. Just as you said, a calorie from fat is much more expensive than a calorie from corn. Nelson Ruiz Nutrition, LLC, Suwanee, GA USA.

Nelson Ruiz very interesting feeding programs tables to compare!! Does the final cost of feed per kg of live broiler include manufacturing and delivery to the broiler farm? Because higher FCR translates into more tons made and shipped, so although on paper it makes sense, the final cost may be different.

The minimum cost per balanced calorie tells us what the "technical optimum cost" is but, as the microeconomic theory tells us, the "maximum benefit" is where the "marginal cost" cuts the "marginal income ($/kg)" curve and this happens after the "optimal technical cost" has been reached.

My source: Microeconomic Theory a Mathematical Approach, J.M.Henderson; Richard Quandt.

In order to compare the performance of different grow-out flocks, I use the same equation as Dr. Víctor Guevara Carrasco.

I would like to add a few more comments to “Economics of Poultry Feeding”.

First, I agree with Dr. Victor Guevara Carrasco's work on this subject, in fact it is similar to my presentation at the Congreso de Empresas Argentinas de Nutrición Animal (CAENA 2017) “Medición de la Productividad en lotes de Parrilleros” (Productivity Measurement in Broiler Flocks).

Second, I also think that it is interesting and correct as Dr. Park Waldroup says to formulate for the “balanced calorie cost” especially in times of low prices for chicken meat.

In this case, it is necessary to calculate the change in feed conversion (FCR) in order to

make the right decision.

Both approaches complement each other very well, the second one to design the best feeding program and the first one to evaluate the results of different flocks.

That has been a wonderful line of discussion to follow. I would like to correct Dr. Guevara's statement, "Commercial softwares have not been developed yet". There are actually quite a few developed and in use by poultry companies around the world. Dr. Ivey, for example, developed two and my company also did the same.

Completely agree with Dr. Ivey's observation that the optimization problem is really much more complex than stated. Energy and ideal protein have to be optimized together (not on a fixed ratio) since there exists interaction between both, especially for feed intake. Impact on yields are also fundamental as they affect revenues. Customization for a given company (actually for each slaughtering plant) situation is fundamental. More complicated yet is that the responses for ideal protein is different for different breeds, response to energy is different between mash and pelleted diets and response to both is different in different ages and sex.

Depending of the company, it might make more sense to optimize the problem considering age as fixed or body weight as fixed variable. Finally, optimizing for the average bird (as most models do) or optimizing the whole production system taking in account available barn area, planned slaughtering number, downtime, placement density and age can be produce quite different outcomes, especially if we consider that changing parameters like downtime (to accommodate eventual changes in age) may also impact performance (where litter is reused).

I am enjoying very much all this discussion. Thanks, Dr. Guevara for bringing your paper to this forum. Just to reinforce, least cost feed formulation starts with different paradigms that are difficult to make broad comparisons. The ingredient data base, with nutrient composition is, most of the time, not adjusted in a real time situation. Also, not all companies have strong laboratory support to update values based on energy (calculated) and nutrient changes (and anti nutritional components - soybean antitrypsins). Besides, each nutritionist has his own energy and nutrient requirements, per phase. The energy and nutrients maximum and minimum vary. The phases are not the same, the breeds vary, even in the same company, etc. So, to get to the point to calculate the final minimum cost of broiler production (cost or margin), we need to go and find environmental interference to the equation, as Alvaro indicated, to reinforce the real gains. By the end of the day, as a business, the companies need to look for the maximum benefits of its assets, that will come, besides what was said before, on feed conversion per square meter, per year. I can have the best cost calculated, but I am not using efficiently the space that the company has available. This is the reason that least cost feed formulation is a tool that must be customized and when we use non linear approach, the customization is more important yet.

Dear Frank, I have been reading what the Feed2Gain does and I would like to know if it is possible to see an example of a printout with the results and information it gives. Also if there is a demo available. Thank you and regards

Very interesting paper, educative, motivating and encouraging. Am looking forward for more to come insha Allah. My best regards.

I made a video and provided an update on different managerial targets in poultry feeding chronologically. I have discussed the least-cost and maximum profit feed formulation in this video. In addition, I have focused on the most recent (2020) targets which have been defined as managerial targets in the field of poultry nutrition.

The video is accessible via the following link: https://youtu.be/oXQaMWv6OiY.

I welcome further discussion and constructive comments on this topic.

Helen Ajayi Thank you so much for your feedback! I have explained how to make a maximum profit feed formulation spreadsheet in this video: (https://youtu.be/33sjsiy_6ck)

Thanks again!

Dr. Afrouziyeh has been of great service to provide a recipe and instruction for creating a non-linear least cost formulation for those that are less certain of the nutritional content of their feeds. The more variation one experiences in the ingredients they buy, the more chance there is, with linear programming, to reach a feed that fails dramatically, as Dr. Waldroup pointed out earlier. When using NIR, for example, with low variation because one has measured the needed values, the least cost linear formulation will give about the same solution as the non-linear as the linear assumes no variation which is approached by low variation.

One other area worth exploring is when to change from one feed to the next, less dense and usually less expensive diet. Real savings can be made there, as well. The practice when Park and I first met was to change feeds around 21 days of age, now it is much earlier. The question that we need to answer is how early. Most Nutritionists have a first diet that they have spent a lot of time developing and, even if lower costs could be generated, the amount fed keeps the cost mitigates the risk involved in making it cheaper. But changing from that diet at the earliest acceptable time will help reduce costs.

Frank Ivey

New nutritional solution in heat stress management. <i>Ganoderma lucidum</i>: An ally to fight heat stress

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)