PRRS control and eradication options for breed to wean farms

Published: April 14, 2014

By: Clayton Johnson,1 DVM; Jean- Paul Cano,2 DVM, PhD

1The Maschhoffs, LLC, Carlyle, Illinois; 2Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Inc., St. Joseph, Missouri

Introduction

The swine veterinarian is charged with delivering optimal health management in a socially and economically sustainable manner. This expectation is complicated by the lack of available evidence for disease prevention, control and treatment forcing the swine veterinarian to regularly make decisions with less than ideal evidence. Never is this complication more evident than in the face of epidemic disease on a Breed to Wean (BTW) farm. A novel porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) introduction on a BTW farm results in dramatic performance losses that with or without intervention threaten farm and producer viability. In the face of this challenge the swine veterinarian must craft a health management plan which optimizes the client’s biological and economic performance. To maximize BTW farm efficiency in the face of a novel PRRSV infection, the swine veterinarian must apply the best available evidence to their decision making process, and ultimately to their health management recommendations. This paper will communicate how The Maschhoffs health team has used best available evidence to control and eradicate PRRSV from BTW farms in our system, and specifically how we have applied learning’s from the Time to Negative Pig Study conducted by the University of Minnesota. PRRS control and eradication options presented below will focus on a Load, Close and Expose (LCE) model of PRRS management, with particular consideration given to two key decision points; the final goal of the PRRS management plan (PRRS Control vs. PRRS Eradication), and the method of BTW herd exposure (Live Virus Inoculation vs. Modified Live Virus Vaccination).

The swine veterinarian is charged with delivering optimal health management in a socially and economically sustainable manner. This expectation is complicated by the lack of available evidence for disease prevention, control and treatment forcing the swine veterinarian to regularly make decisions with less than ideal evidence. Never is this complication more evident than in the face of epidemic disease on a Breed to Wean (BTW) farm. A novel porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) introduction on a BTW farm results in dramatic performance losses that with or without intervention threaten farm and producer viability. In the face of this challenge the swine veterinarian must craft a health management plan which optimizes the client’s biological and economic performance. To maximize BTW farm efficiency in the face of a novel PRRSV infection, the swine veterinarian must apply the best available evidence to their decision making process, and ultimately to their health management recommendations. This paper will communicate how The Maschhoffs health team has used best available evidence to control and eradicate PRRSV from BTW farms in our system, and specifically how we have applied learning’s from the Time to Negative Pig Study conducted by the University of Minnesota. PRRS control and eradication options presented below will focus on a Load, Close and Expose (LCE) model of PRRS management, with particular consideration given to two key decision points; the final goal of the PRRS management plan (PRRS Control vs. PRRS Eradication), and the method of BTW herd exposure (Live Virus Inoculation vs. Modified Live Virus Vaccination).

System PRRS management background

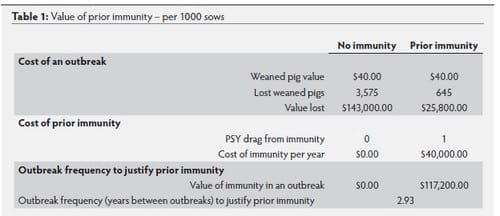

PRRS impact on a BTW farm is most noticeable during the acute outbreak, and our system has historically modeled biologic and economic performance relative to growing pig losses, specifically post-weaning mortality. Accordingly, the health team’s recommendation for PRRS management following a novel PRRSV introduction has been based on PRRS elimination to most rapidly achieve PRRSV negative piglet production, described in the Time to Negative Pig Study as Time to PRRSV Stability (TTS). Herds achieve “TTS status” when there is a failure to detect PRRSV RNA in serum of pre-weaning pigs by PCR over a 90-day period, following the AASV PRRSV-status criteria for a category IIB herd. The value of prior herd immunity (defined as decreased total preweaning piglet losses and decreased TTS) has been harder to quantify and therefore not valued in previous PRRS control bio-economic models. The Time to Negative Pig Study provides quantified estimates of Time to Baseline Production (TTBP) and TTS associated with various PRRS management strategies as well as previous herd immunity to PRRSV. Adding this information to our model and therefore to our decision making process allows valuation of the PRRSV negative weaned pig in relation to total sow farm losses assuming the BTW herd has either previous immunity or no immunity to PRRSV.

Updated PRRSV impact estimates

Time to Negative Pig Study updates provided in November, 2012 supported the quantification of two critical decision making points in PRRS management, the method of exposure (Live Virus Inoculation vs. Modified Live Virus Vaccination) as well as the value of prior immunity (PRRSV antibody positive vs. PRRSV antibody negative) in the face of subsequent novel PRRSV infections. TTS and TTBP were quantified for each option using median results of reported data. The resulting model outputs have truly revolutionized our approach to PRRS management. It is important to note that like all studies, the Time to Negative Pig Study has limitations. Specifically, participant herds were not randomly allocated to treatment, therefore the comparison relies on observational analysis and association does not infer causation. There is high variability and low control of loading, exposure and sampling methods. The TTBP estimates make major assumptions and do not consider the impact of other infectious agents present within a BTW herd. Finally, genetics, nutrition, environmental factors and numerous other variables are not controlled. Despite these challenges, our team has identified this to be the “best available information” and in the spirit of evidence based medicine, we will utilize this resource until superior evidence is presented.

PRRS impact on a BTW farm is most noticeable during the acute outbreak, and our system has historically modeled biologic and economic performance relative to growing pig losses, specifically post-weaning mortality. Accordingly, the health team’s recommendation for PRRS management following a novel PRRSV introduction has been based on PRRS elimination to most rapidly achieve PRRSV negative piglet production, described in the Time to Negative Pig Study as Time to PRRSV Stability (TTS). Herds achieve “TTS status” when there is a failure to detect PRRSV RNA in serum of pre-weaning pigs by PCR over a 90-day period, following the AASV PRRSV-status criteria for a category IIB herd. The value of prior herd immunity (defined as decreased total preweaning piglet losses and decreased TTS) has been harder to quantify and therefore not valued in previous PRRS control bio-economic models. The Time to Negative Pig Study provides quantified estimates of Time to Baseline Production (TTBP) and TTS associated with various PRRS management strategies as well as previous herd immunity to PRRSV. Adding this information to our model and therefore to our decision making process allows valuation of the PRRSV negative weaned pig in relation to total sow farm losses assuming the BTW herd has either previous immunity or no immunity to PRRSV.

Updated PRRSV impact estimates

Time to Negative Pig Study updates provided in November, 2012 supported the quantification of two critical decision making points in PRRS management, the method of exposure (Live Virus Inoculation vs. Modified Live Virus Vaccination) as well as the value of prior immunity (PRRSV antibody positive vs. PRRSV antibody negative) in the face of subsequent novel PRRSV infections. TTS and TTBP were quantified for each option using median results of reported data. The resulting model outputs have truly revolutionized our approach to PRRS management. It is important to note that like all studies, the Time to Negative Pig Study has limitations. Specifically, participant herds were not randomly allocated to treatment, therefore the comparison relies on observational analysis and association does not infer causation. There is high variability and low control of loading, exposure and sampling methods. The TTBP estimates make major assumptions and do not consider the impact of other infectious agents present within a BTW herd. Finally, genetics, nutrition, environmental factors and numerous other variables are not controlled. Despite these challenges, our team has identified this to be the “best available information” and in the spirit of evidence based medicine, we will utilize this resource until superior evidence is presented.

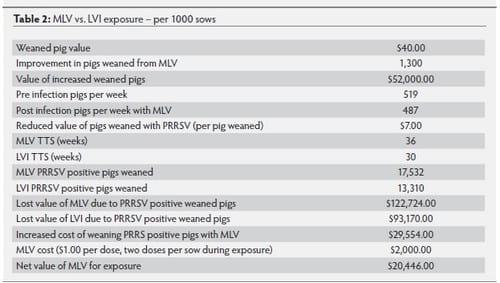

Our updated impact estimates can be most easily explained relative to biologic performance. When reviewing the associations with TTS, our group noted that consistent with The Maschhoffs experiences, tremendous variability in TTS existed throughout the industry. Regardless of the variability in TTS, two significant associations could be made:

• BTW herds implementing Live Virus Inoculation (LVI) for exposure achieved TTS significantly faster than comparable herds achieving stabilization through Modified Live Virus (MLV).

• BTW herds with prior immunity (defined as PRRSV antibody positive at the time of novel PRRSV introduction) had achieved TTS significantly faster than comparable herds without prior immunity (defined as PRRSV antibody negative at the time of novel PRRSV introduction).

When reviewing the associations with TTBP (defined as 21 week performance of the affected farm prior to novel PRRSV outbreak), we noted several critical findings:

• TTS was poorly correlated with TTBP.

• TTBP was highly correlated with total pre-weaning production losses.

• Prior herd immunity resulted in earlier TTBP, with a drastic increase in total weaned piglet production relative to PRRSV naïve herds and an apparent dose impact with herds exposed multiple times reaching TTBP sooner than herds exposed once.

• BTW herds using MLV reached TTBP significantly faster than herds using LVI.

The following tables (Table 1 and Table 2) reflect our updated assumptions used to evaluate the biologic and economic performance of BTW farms engaging in an LCE PRRS management strategy utilizing LVI or MLV as their exposure method. These models assume that the

same minimum criteria defined for inclusion in the Time to Negative Pig Study are in place and that the BTW farm currently experiencing a novel PRRSV infection flawlessly implements MCREBEL practices throughout herd closure.

These assumptions and associated economic impacts have resulted in two dramatic changes in PRRS management on BTW farms. We first changed our method of exposure from LVI to MLV on all BTW farms implementing an LCE PRRS management program. While our assumption that LVI would result in faster TTS was correct, the value of the increased PRRSV naïve weaned piglets was less than the value of faster TTBP and the associated increased weaned piglet production during herd closure. We continue to challenge the model as the value of a weaned pig changes, but the model is insensitive to weaned pig values, resulting in consistent PRRS management recommendations regardless of the current weaned pig price. Our second dramatic change was a transition from exclusive use of an “Eradication” approach to PRRS management to a decision making process that uses historical PRRS “outbreak frequency” to determine whether PRRS management attempts will result in Control (PRRSV vaccinated gilt introductions) or Eradication (PRRSV negative gilt introductions). Given that BTW herds regularly challenged by novel PRRSV introductions have inherently more value in being PRRSV antibody positive, we found the point of inflection in our model at which the benefits of decreased performance losses associated with each novel PRRSV introduction outweigh the cost of maintaining PRRS immunity in the BTW herd. For the purposes of our very basic model, this break frequency is approximately 1 novel PRRSV introduction every three years. Farms with a historic outbreak frequency of less than one outbreak every three years create more value by Eradicating PRRSV and farms with a historic outbreak frequency of more than one outbreak every three years create more value by Controlling PRRSV. This assumes that the historic outbreak frequency is an accurate predictor of future break frequency, an assumption that should be challenged regularly by the veterinarian working with the impacted herd.

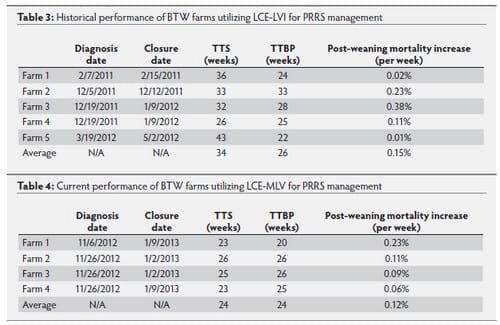

Historical vs. current performance

While caution should be taken in comparing biological performance between historical and current PRRS management strategies, it is good practice to evaluate actual results in relation to model assumptions. Such information provides a quantitative “response to therapy” that can

assist continuous improvement of PRRS management decision making and at a minimum, can point to specific model assumptions which need further validation. The performance data listed below represents the impact of novel PRRSV infection on a Maschhoffs BTW farm using

an LCE PRRS management strategy utilizing LVI (Historical) vs. MLV (Current) as our exposure method. Results of biologic performance are presented specific to one BTW herd and include the herds TTS, TTBP and Post-Weaning Mortality. Definitions for these performance metrics are listed below:

TTS – Number of weeks from herd closure (date of exposure followed by no live animal introductions) until the achievement of PRRSV status category IIB. Category IIB represents the time at which pre-weaning piglet testing for PRRSV has provided evidence of decreased PRRSV transmission to allow for negative (Eradication) or vaccinated (Control) gilt entry and subsequent sentinel testing.

• BTW herds implementing Live Virus Inoculation (LVI) for exposure achieved TTS significantly faster than comparable herds achieving stabilization through Modified Live Virus (MLV).

• BTW herds with prior immunity (defined as PRRSV antibody positive at the time of novel PRRSV introduction) had achieved TTS significantly faster than comparable herds without prior immunity (defined as PRRSV antibody negative at the time of novel PRRSV introduction).

When reviewing the associations with TTBP (defined as 21 week performance of the affected farm prior to novel PRRSV outbreak), we noted several critical findings:

• TTS was poorly correlated with TTBP.

• TTBP was highly correlated with total pre-weaning production losses.

• Prior herd immunity resulted in earlier TTBP, with a drastic increase in total weaned piglet production relative to PRRSV naïve herds and an apparent dose impact with herds exposed multiple times reaching TTBP sooner than herds exposed once.

• BTW herds using MLV reached TTBP significantly faster than herds using LVI.

The following tables (Table 1 and Table 2) reflect our updated assumptions used to evaluate the biologic and economic performance of BTW farms engaging in an LCE PRRS management strategy utilizing LVI or MLV as their exposure method. These models assume that the

same minimum criteria defined for inclusion in the Time to Negative Pig Study are in place and that the BTW farm currently experiencing a novel PRRSV infection flawlessly implements MCREBEL practices throughout herd closure.

These assumptions and associated economic impacts have resulted in two dramatic changes in PRRS management on BTW farms. We first changed our method of exposure from LVI to MLV on all BTW farms implementing an LCE PRRS management program. While our assumption that LVI would result in faster TTS was correct, the value of the increased PRRSV naïve weaned piglets was less than the value of faster TTBP and the associated increased weaned piglet production during herd closure. We continue to challenge the model as the value of a weaned pig changes, but the model is insensitive to weaned pig values, resulting in consistent PRRS management recommendations regardless of the current weaned pig price. Our second dramatic change was a transition from exclusive use of an “Eradication” approach to PRRS management to a decision making process that uses historical PRRS “outbreak frequency” to determine whether PRRS management attempts will result in Control (PRRSV vaccinated gilt introductions) or Eradication (PRRSV negative gilt introductions). Given that BTW herds regularly challenged by novel PRRSV introductions have inherently more value in being PRRSV antibody positive, we found the point of inflection in our model at which the benefits of decreased performance losses associated with each novel PRRSV introduction outweigh the cost of maintaining PRRS immunity in the BTW herd. For the purposes of our very basic model, this break frequency is approximately 1 novel PRRSV introduction every three years. Farms with a historic outbreak frequency of less than one outbreak every three years create more value by Eradicating PRRSV and farms with a historic outbreak frequency of more than one outbreak every three years create more value by Controlling PRRSV. This assumes that the historic outbreak frequency is an accurate predictor of future break frequency, an assumption that should be challenged regularly by the veterinarian working with the impacted herd.

Historical vs. current performance

While caution should be taken in comparing biological performance between historical and current PRRS management strategies, it is good practice to evaluate actual results in relation to model assumptions. Such information provides a quantitative “response to therapy” that can

assist continuous improvement of PRRS management decision making and at a minimum, can point to specific model assumptions which need further validation. The performance data listed below represents the impact of novel PRRSV infection on a Maschhoffs BTW farm using

an LCE PRRS management strategy utilizing LVI (Historical) vs. MLV (Current) as our exposure method. Results of biologic performance are presented specific to one BTW herd and include the herds TTS, TTBP and Post-Weaning Mortality. Definitions for these performance metrics are listed below:

TTS – Number of weeks from herd closure (date of exposure followed by no live animal introductions) until the achievement of PRRSV status category IIB. Category IIB represents the time at which pre-weaning piglet testing for PRRSV has provided evidence of decreased PRRSV transmission to allow for negative (Eradication) or vaccinated (Control) gilt entry and subsequent sentinel testing.

TTBP – Number of weeks from herd closure until weekly PSY has returned to baseline performance (defined as the average herd PSY during the 12 months prior to novel PRRSV introduction).

Post-Weaning Mortality Increase– Average weekly mortality increase for all pigs weaned in the first six months immediately following herd closure when compared to the average weekly mortality during the six months immediately prior to novel PRRSV diagnosis.

Post-Weaning Mortality Increase– Average weekly mortality increase for all pigs weaned in the first six months immediately following herd closure when compared to the average weekly mortality during the six months immediately prior to novel PRRSV diagnosis.

Given our recent adoption of PRRSV Control on farms with high historic PRRSV break frequencies, we do not yet have data available on actual impact of prior immunity. We recognize the value in this data, and will monitor performance of PRRSV Control farms in the face of novel PRRSV introductions to challenge our model in a similar manner as our LCE-MLV vs. LCE-LVI approach.

Conclusions

• While ideal evidence to support PRRS management decision making on a BTW farm does not exist, there is an ever growing body of information which should be consulted regularly by the swine veterinarian prior to implementing a PRRS management plan.

• The Time to Negative Pig Study provides performance impact estimates of TTS and TTBP using either LVI or MLV for exposure.

• The Time to Negative Pig Study provides performance impact estimates of TTS and TTBP based on the presence of prior immunity in a BTW herd in the face of a novel PRRSV introduction.

• TTS and TTBP estimates can be used to create biological and economic performance models to improve the quality of decision making prior to implementing a PRRS management plan.

• Using TTS and TTBP estimates, homogenizing a BTW herd through MLV results in more value generation than exposure through LVI in spite of the fact that LVI results in a shorter TTS.

• Using TTS and TTBP estimates, maintaining a PRRSV antibody positive status results in more value generation than eradication of PRRSV on a BTW farm that experiences a novel PRRSV introduction more frequently than once every three years.

Content from the event:

Authors:

Carthage Veterinary Service, Ltd.

Boehringer Ingelheim

Recommend

Comment

Share

Would you like to discuss another topic? Create a new post to engage with experts in the community.