Beneficial Yeast: New weapon to combat Aspergillus Flavus

Published: July 25, 2012

By: Marcia Wood (Agricultural Research Service, USDA)

Tomorrow's orchards of almonds, pistachios, and walnuts might be sprayed with fine mists of a beneficial yeast, Pichia anomala. Studies led by Agricultural Research Service plant physiologist Sui-Sheng T. (Sylvia) Hua have shown that this yeast can undermine a troublesome mold, Aspergillus flavus. The mold is of concern because it produces aflatoxin, a natural carcinogen.

Federal food safety standards and quality-control procedures at U.S. packinghouses help ensure that these crunchy, healthful tree nuts remain safe to eat. Nonetheless, growers and processors have a continuing interest in new, environmentally friendly ways to combat the mold.

Hua is one of several scientists at ARS's Western Regional Research Center in Albany, California, who are investigating new strategies for thwarting A. flavus.

The idea of developing a practical, affordable way for growers to use a yeast to fight a mold isn't new. But Hua's tree-nut-focused investigations of P. anomala may be among the most extensive of their kind to date.

Her research has included exploring the yeast's talents as a biocontrol candidate in a series of laboratory tests at Albany and in a field test at a California pistachio orchard. The orchard study, documented in a patent issued to Hua in 2009, indicated that the yeast was responsible for a 96-percent reduction in the number of mold spores.

For ongoing laboratory research, Hua has selected, refined, and applied several analytical procedures to discover precisely how the yeast disables the mold. "If we understand the underlying mechanisms," she says, "we may be able to use that knowledge to increase the yeast's effectiveness."

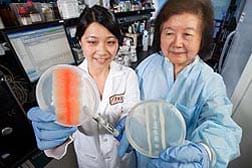

Plant physiologist Sylvia Hua (right) and technician Siov Sarreal display petri dishes showing the effectiveness of a biocontrol yeast against Aspergillus flavus. On the left, a mutant A. flavus turns the agar orange, signifying aflatoxin production. On the right, when the same A. flavus was inoculated between two streaks of yeast, growth was inhibited and no aflatoxin was produced.

In a collaborative experiment with Albany coinvestigators Bradley J. Hernlem, a chemical engineer; and Maria T. Brandl, a microbiologist, the mold was exposed to the yeast and later to several different compounds that fluoresce red or green when evidence of specific changes in the mold's cells is detected.

Results of these assays, documented in a peer-reviewed article in the scientific journal Mycopathologia, suggest that the yeast interfered with the mold's energy-generating ATP (adenosine triphosphate) system, vital for the mold's survival. The findings also suggest that the yeast damaged mold cell walls and cell membranes. Walls and membranes perform the essential role of protecting cell contents.

The team used a different analytical procedure—quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (polymerase chain reaction) assays—to analyze the activity of certain P. anomala genes in the presence of the mold. Preliminary findings, which Hua reported at the annual national meeting of the American Society for Microbiology in 2010, suggest that exposing the yeast to the mold may have triggered the yeast to turn on genes that code for production of two enzymes—PaEXG1 and PaEXG2.

"These enzymes are capable of degrading the mold's cell walls and causing damage to membranes," Hua notes.

Though further studies are needed, Hua says these early, PCR-based findings point to "gene-controlled mechanisms that may be involved in the cell wall and cell membrane damage observed in the fluorescence assays."

This research supports the USDA priority of ensuring food safety and is part of Food Safety, an ARS national program (#108) described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

This article was originally published in the U.S Department of Agriculture´s science magazine, Agricultural Research, July 2012 Issue. Engormix.com thanks for this huge contribution.

Source

Marcia Wood (Agricultural Research Service, USDA)Related topics:

Recommend

Comment

Share

25 de julio de 2012

S. Nada, H. Amra, M. Y. Deabes & E. Omara (2010) Saccharomyces Cerevisiae And Probiotic Bacteria Potentially Inhibit Aflatoxins Production In Vitro And In Vivo Studies. The Internet Journal of Toxicology. 2010 Volume 8 No.1 http://www.ispub.com/journal/the_internet_journal_of_toxicology/volume_8_number_1_32/article/saccharomyces-cerevisiae-and-probiotic-bacteria-potentially-inhibit-aflatoxins-production-in-vitro-and-in-vivo-studies.htm

Abstract

Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus rhamnosus LC705) potentially inhibited Aspegillus flavus growth and aflatoxins production in YES liquid media. Six groups of rats orally administrated SC (1011 CFU / ml) and LGG & LC705 (109 CFU/ ml) daily for 15 days alone or with 2 mg / ml aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) in corn oil, significantly reduced serum ALT, AST, GGT, creatinine, and BUN compared with AFB1-tereated group. No deaths occurred in any combined treatment with AFB1, while a 30% mortality rate was recorded in the AFB1-treated group. Blood glutathione (GSH) levels significantly increased in groups treated with single-treatment of S. cerevisiae, LGG & LC705 or concomitant with AFB1; however, AFB1-treatment alone severely depleted GSH level more than other treatments. Histopathological examination of liver and kidney in rats treated with AFB1 showed necrosis, vacuolar degeneration and fatty changes in hepatocytes; cellular swelling and pyknotic nuclei of proximal convoluted tubules in renal tissue. DNA content decreased significantly in liver and kidney tissues with AFB1-administration, these findings were ameliorated by probiotec bacteria and S.cervisiae treatment. Conclusion: These probiotics may have good medical benefits to diminish the aflatoxins production in vitro and in vivo studies.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Recommend

Reply

Would you like to discuss another topic? Create a new post to engage with experts in the community.