Effect of Dietary Melatonin and L-Tryptophan on Growth Performance and Immune Responses of Broiler Chicken under Experimental Aflatoxicosis

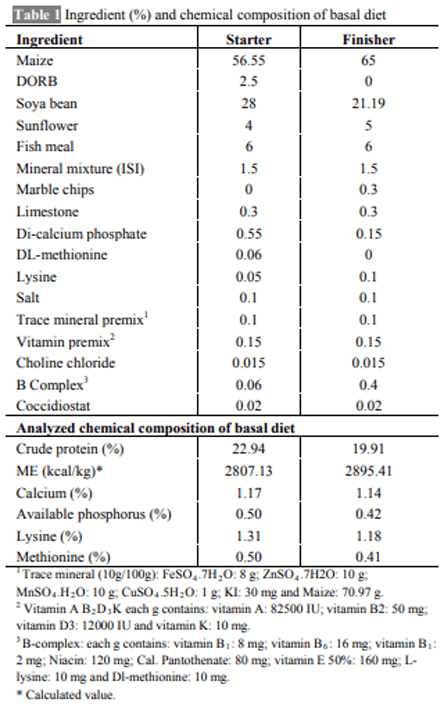

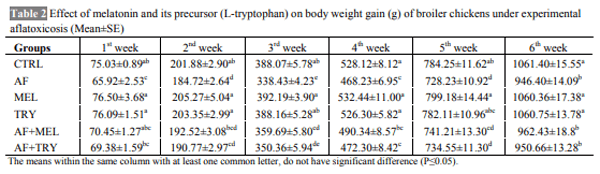

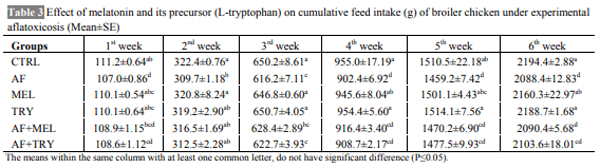

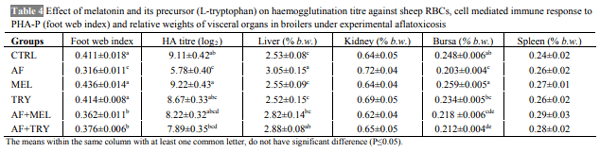

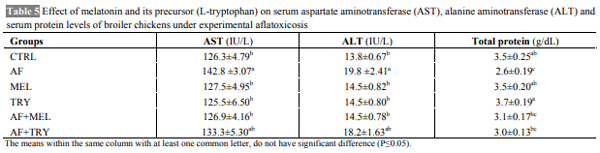

The aim of the present work was to determine whether the administration of melatonin or L-tryptophan (a precursor of melatonin) affects the immune responses and performance of broilers during induced exposure to aflatoxins in feed. The study was conducted from 0-6 weeks comprising six dietary treatments in triplicate with 10 chickens in each replicate. The diets were formulated to supply 23% crude protein (CP) and 2800 kcal ME/kg in starter ration and 20% CP and 2900 kcal ME/kg in finisher ration. The experimental diets were offered ad libitum with free access to water throughout the entire experiment. Inclusion of aflatoxin in the feed at 0.5 mg/kg feed caused a significant reduction in the growth performance of broilers. Supplementation of melatonin (20 mg/kg in feed and 20 mg/kg body weight through i.p. route) or its precursor (L-tryptophan at 250 mg/kg feed) in aflatoxin fed broilers resulted in numerically improved performance. Aflatoxin inclusion in the feed also caused a significant reduction in haemagglutination titer against sheep RBC and cell mediated immune responses to phytohemagglutinin (PHA-P) in broilers. Melatonin or L-tryptophan inclusion in toxin incorporated feed significantly improved both humoral and cell mediated immunity. No significant (P>0.05) differences were observed among various groups with respect to kidney and spleen weight but liver weight increased significantly (P≤0.05) and weight of bursa significantly decreased upon aflatoxin inclusion. Our study suggests that L-tryptophan was partially as effective as melatonin in alleviating aflatoxin induced growth retardation and immunosuppression in broiler chicken.

KEY WORDS aflatoxin, broilers, immunity, L-tryptophan, melatonin, performance.

AOAC. (1991). Official Methods of Analysis. Vol. I. 15th Ed. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Arlington, VA.

Bakshi C.S. (1991). Studies on the effect of graded dietary levels of aflatoxin on immunity in commercial broilers. MS Thesis. Indian Veterinary Research Institute. lzatnagar, U.P., India.

Balachandran C. and Ramakrishnan R. (1987). An experimental study on the pathology of aflatoxicosis in broiler chickens. Indian Vet. J. 64, 911-914.

Beura C.K., Johri I.S., Sadagopan V.R. and Panda B.K. (1993). Interaction of dietary protein level on dose-response relationship during aflatoxicosis in commercial broilers. Indian J. Poult. Sci. 28, 170-177.

Brennan C.P., Hendricks G.L., EI-Sheikh T.M. and Mashaly M.M. (2002). Melatonin and the enhancement of immune response in chickens. Poult. Sci. 81, 371-375.

Brown T. (1996). Fungal diseases. Pp. 305-315 in Poultry Diseases, F.T.W. Jordan and M. Puttison Eds. Jordan, Saunders W.B. Ltd. Site of publication.

Bubenik G.A. (2002). Gastrointestinal melatonin. Localization, function and clinical relevance. Dig. Dis. Sci. 47, 2336-2348.

Calvo J.R., Reiter R.J., García J.J., Ortiz G., Tan D.X. and Karbownik M. (2001). Characterization of the protective effects of melatonin and related indoles against alpha naphthyl isothiocyanate-induced liver injury in rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 80, 461- 470.

Chattopadhyay S.K., Taskar P.K., Schwabe O., Das Y.T. and Brown H.D. (1985). Clinical and biochemical effects or aflatoxin in feed ration of chicks. Cancer. Biochem. Biophys. 8, 67-75.

Chen C., Pearson A.M., Coleman T.H., Gray J.I. and Wolzak A.M. (1985). Broiler aflatoxicosis with recovery after replacement of the contaminated diet. Brit. Poult. Sci. 26, 65-71.

Choy W.N. (1993). A review of the dose-response induction of DNA adducts by aflatoxin B1 and its implications in quantitative cancer risk. Mut. Res. 296, 181-198.

Cole R.J. and Cox R.H. (1981). The aflatoxins. Handbook of Toxic Fungal Metabolites. Academic Press, New York, NY. Pp. 1-66.

Corrier D. and DeLoach J.R. (1990). Evaluation of cell mediated cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity in young chickens by an interdigital skin test. Poult. Sci. 69, 403-408.

Coulombe R.A. (1994). Non hepatic disposition and effects of aflatoxin B1. Pp. 89-101 in The Toxicology of Aflatoxins: Human Health, D.L. Eaton and J.D. Groopman Eds. Veterinary and Agricultural Significance, Academic Press, San Diego, California, USA.

Esteban S., Nicolaus C., Garmundi A., Rial R.V., Rodríguez A.B., Ortega E. and Ibars C. (2004). Effect of orally administered Ltryptophan on serotonin, melatonin, and the innate immune response in the rat. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 267, 39-46.

Firozi P.F. and Bhattacharya R.K. (1995). Effects of natural polyphenols on aflatoxin B1 activation in a reconstituted microsomal monooxygenase system. J. Biochem. Toxicol. 10, 25-31.

Gabal M.A. and Azzam A.H. (1998). Interaction of aflatoxin in the feed and immunization against selected infectious diseases in poultry. II Effect on one-day-old layer chicks simultaneously vaccinated against Newcastle disease, infectious bronchitis and infectious bursal disease. Avian Pathol. 27, 290-295.

Gopi K. (2006). Influence of melatonin on aflatoxicosis in broiler chicken. MS. Thesis. Deemed University, IVRI, Izatnagar.

Groopman J.D., Wang J.S. and Scholl P. (1996). Molecular bio- markers for aflatoxins: from adducts to gene mutations to hu- man liver cancer. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 74, 203-209.

Herichova I., Zeman M. and Veselovsk J. (1998). Effect of trypto- phan administration on melatonin concentrations in the pineal gland, plasma and gastrointestinal tract of chickens. Acta. Vet. Brno. 67, 89-95.

Krystyna S.S. (2002). Melatonin in immunity: comparative as- pects. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 23, 61-66.

Maestroni G.J.N. (1995). T-Helper-2 lymphocytes as a peripheral target of melatonin. J. Pineal. Res. 18, 84-89.

Moore C.B. and Siopes T.D. (2000). Effects of light conditions and melatonin supplementation on the cellular and humoral immune responses in Japanese quail. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 119, 95-104.

Moss M.O. (1996). Centenary Review: Mycotoxins. Mycol. Res. 100, 513-523.

Nabney J. and Nesbitt B.F. (1965). A spectrophotometric method for determining the aflatoxins. Analyst. 90, 155-160.

Nath R. (2008). Changes in the serum enzymes during ex- perimental aflatoxicosis in broiler chicken. Indian Vet. J. 85, 10-12.

Pieri C., Marra M., Moroni F., Recchioni R. and Marcheselli F. (1994). Melatonin: a peroxyl radical scavenger more effective than vitamin E. Life. Sci. 55, 271-276.

Pons W.A., Cucullua F.A., Lee L.S., Robertson J.A., Franz S.O. and Goldblatt L.A. (1966). Determination of aflatoxins in ag- ricultural products: use of aqueous acetone for extraction. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 49, 554-562.

Raju M.V.L.N. and Devegowda G. (2000). Influence of modified glucomannan on performance, organ morphology, serum bio- chemistry and hematology in broilers exposed to individual and combined mycotoxicosis. Br. Poult. Sci. 41, 640-650.

Reddy A.R., Reddy V.R., Rao P.V. and Yadagiri B. (1982). Effect of experimentally induced aflatoxicosis on the performance of commercial broiler chicks. Indian J. Anim. Sci. 52, 405-410.

Rosa C.A., Miazzo R., Magnoli C., Salvano M., Chiacchiera S.M., Ferrero S., Sáenz M., Carvalho E.C. and Dalcero A. (2001). Evaluation of the efficacy of bentonite from the south of Ar- gentina to ameliorate the toxic effects of aflatoxin in broilers. Poult. Sci. 80, 139-144.

Shotwell O.L., Hesseltine C.W., Stubblefield R.D. and Sorenson W.G. (1966). Production of aflatoxin on rice. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 425-428.

Siegel P.B. and Gross W.B. (1980). Production and persistence of antibodies in chicken to sheep erythrocytes. 1. Directional se- lection. Poult. Sci. 59, 1-5.

Snedecor G.W. and CochranW.G. (1989). Statistical Methods. 8th Ed. Oxford and ISH Publishing Co., Cal- cutta.

Thakur R. (2004). Effect of pinealectomy and exogenous mela- tonin on jejunal melatonin and digestive enzyme levels in broiler. MS Thesis. Deemed University, IVRI, Izatnagar.

Verma J. (1994). Studies on the effect of dietary aflatoxin, ochratoxin and their combinations on performance energy and pro- tein utilization in poultry. Ph D. Thesis. Deemed University, IVRI, Izatnagar.

Virdi J.S., Tiwari R.P., Saxena M., Khanna V., Singh G., Saini S.S. and Vadehra D.V. (1989). Effects of aflatoxin on the immune system of the chick. J. Appl. Toxicol. 9, 271-275.

Zeman M., Buyse J., Herichova I. and Decuypere E. (2001). Mela- tonin decreases heat production in female broiler chickens. Acta Vet. Brno. 70, 15-18.