Introduction

Eggshell quality is an important parameter to insure egg safety for consumers and to optimize hatchability and chick quality and is increasingly becoming a decisive parameter for the profitability of the poultry industry due to prolonged cycles of production.

Eggshell quality can be defined by different parameters:The specific gravity of the egg (Ingram et al., 2008) is a parameter that was used in the hatching industry as an indicator for shell thickness.Mauldin (1994) investigated the effect of specific gravity on bacterial penetration and concluded that eggs with low specific gravity suffered between 2 and 3 times more bacterial penetration after 30 minutes up to 24 hours of storage than eggs with a high specific gravity.

Bennet (1992) indicated that eggs defined as thin had much lesser hatchability than eggs classified as a thick shell and the effect was much higher at the end of the production cycle than in the hatchability peak period.Shell weight and shell %, breaking strength of the shell, shell deformation (SD) shell reflectivity and shell color (Roberts, 2005) and dynamic tension (Dunn et al., 2005) also define eggshell quality.

In addition to eggshell quality, albumen quality is also an important parameter to insure egg safety for consumers and to optimize hatchability and chick quality.This can be explained by their anti-bacterial effects (Ingram et al., 2008; Lourens, 2008), and its effect on the calcification process (Hunton, 1995).

Albumen quality is determined mainly by Haugh units (HU) (Roberts, 2005).During the storage of eggs for hatching, the HU decrease, leading to hatchability reduction (Tona et al., 2002).

Materials & Methods

The objective of this study was to investigate the effect of Shellbiotic on the reproductive parameters of breeding hens for broilers.Shellbiotic is a product based on a specific combination of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) and lactic acid.Two different experiments were conducted from August 2008 until March 2010.

Experiment 1

Held in three farms with 2 identical sheds and each had 7,500, 12,000 or 12,500 birds, respectively.The Ross 308 race was used in all farms. At the beginning of the test the corresponding age of birds was 31 weeks (farm 1), 41 weeks (farm 2) and 45 (farm 3) weeks of age.On each farm, the following treatments were applied:(1) commercial feed for breeders and (2) commercial feed for breeders supplemented with 0.1% of Shellbiotic.At the beginning of the test no abnormalities were observed and all the sheds were managed in accordance with recommendations for the Ross 308 race. The daily production per hen (HDP) and % of mortality on all farms were measured daily.Likewise, the % of broken eggs and egg weight were measured daily on farms 2 and 3. At the beginning of the test 60 eggs in each group were randomly selected and their weight, SD and HU were analyzed.This was repeated each month during the trial period.The eggs that were used for the analysis were fresh eggs (1 day old and stored in the cold room).The trial period lasted from 31 weeks up to 59 weeks of age on farm 1, from 41 to 55 weeks old on farm 2 and from 45 to 59 weeks of age on farm 3 weeks. Egg quality data were analyzed according to the Student''''s t test.

Experiment 2

Held on a farm with 2 sheds of 6,000 and 8,000 chickens of the Ross 308 race, respectively already subject to molt.The birds were subjected to molt at the age of 56 weeks and the test began at 80 weeks of age.The following treatments were implemented:(1) commercial feed for breeders and (2) commercial feed for breeders supplemented with 0.1% of Shellbiotic.At the beginning of the test no abnormalities were observed and both sheds were managed according to company standards.At the beginning of the test 60 eggs from each group were randomly selected and the weight of the eggs, SD and HU were analyzed.This was repeated twice during the trial period.The trial period lasted from 80 weeks to 93 weeks of age.At the age of 90 weeks, the effect of Shellbiotic on albumen quality, on the storage of the egg was determined.The eggs were stored at 15 ° C and 70% relative humidity (RH).

Egg quality data were analyzed according to the Student''''s t test.

Results and Discussion

Experiment 1

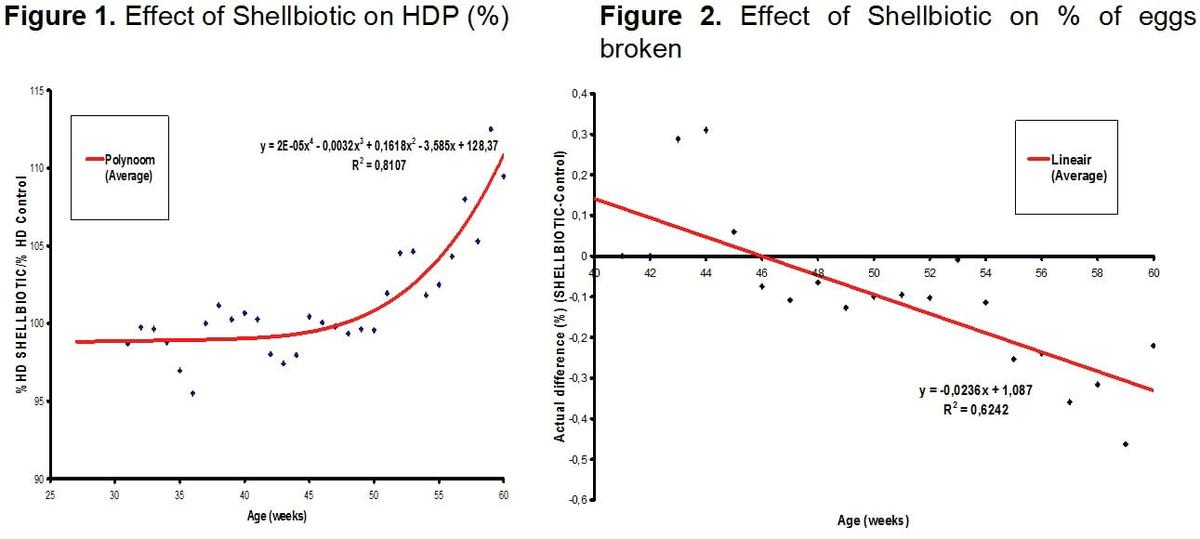

From the hen daily production (HDP) data, expressed as relative performance, the addition of Shellbiotic tends to yield higher production results in comparison with the control group.In addition to this, this difference becomes more pronounced after 45 weeks of age (Fig. 1). This is in line with previous observations with AGCMS (Aromabiotic) on the performance in hens (Huyghebaert, 2007).

There was no effect on mortality and egg weight due to the treatment.Egg weight during the trial period grew according to the expectations of the business.

Figure 2 indicates the % of eggs broken in the operation decreased in the group that received Shellbiotic in comparison with the control group.

There is a correlation between SD and HU (r = - 0.6), indicating that albumen quality is correlated with a better shell quality (lower SD).These observations are in line with Solomon (1991).

The addition of Shellbiotic significantly improved the SD (23.2 µm vs. 25.8 µm, p < 0.05) at the age of 43 weeks (farm 2), 45 and 50 weeks (farm 1) (25.8 µm vs. 28.4 µm and 23 µm vs. 23.3 µm, p < 0.05) and almost significantly (p < 0.10) at the age of 55 weeks on farm 3 (27.8 µm vs. 29.3 µm).Due to a major deviation in different farms the HU improved significantly (p < 0.05) only at the age of 51 weeks on farm 3 (74.8 against 67.1) and nearly significantly in 55 weeks of age (65.2 against 59.8).These results are summarized in Figure 3.

It can be concluded that Shellbiotic improves the quality of egg characteristics, but has no effect on the weight of the eggs. It is suggested that Shellbiotic has an effect on the production process. This may be due to less inflammation reactions and lower physiological stress affecting the neuro-endocrine systems. Further research is needed to verify this.

Experiment 2

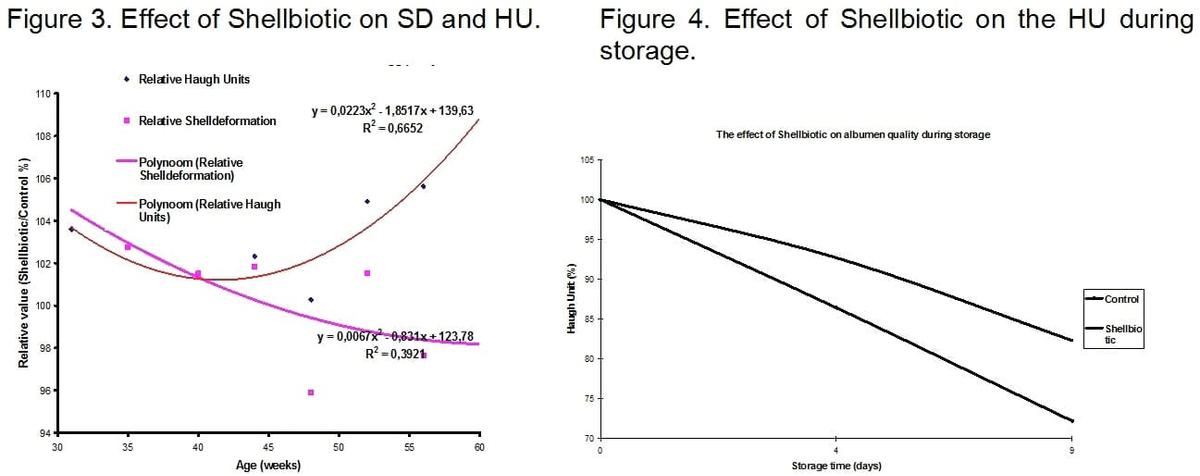

As hatchability and HU diminish during storage, a second experiment was carried out to measure the effect of Shellbiotic on the HU during storage.According to Tona et al.(2002), the longer eggs are stored the lower the HU are (Fig.4).

This effect showed a tendency on day 4 (66.9 vs. 61.9, p = 0.112) and was significant on day 9 (59.5 vs. 51.9, p = 0.031).If, according to Van de Ven (2009) hatchability decreases with storage, it can be concluded that Shellbiotic improves hatchability.

Conclusions

With increasing genetic improvements to increase egg production and lengthen laying periods, egg formation and the calcification process are becoming more critical and could give rise to hatchability and shell quality issues.Improving the quality of the albumen not only improves the hardness of the shell, but also the hatchability and chick quality.These tests indicate that the addition of Shellbiotic to the feed of broiler breeding hens contributes to a better albumen and egg quality and, therefore, has the potential to improve the profitability of the poultry sector.

Bibliography

Bennet CD. 1992. The influence of shell thickness on hatchability in commercial breeder flocks. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 1:61-65.

Dunn IC, Bain M, Edmond A, Wilson PW, Joseph N, Solomon S, De Ketelkaere B, De Baerdemaeker J, Schmutz M, Preisinger R, Waddington D. 2005. Dynamic stiffness (Kdyn) as a predictor of eggshell damage and its potential for genetic selection. XIth European Symposium on the quality of eggs and egg products. Doorwerth, The Netherlands.

Hunton P. 1995. Understanding the architecture of the egg shell. World''''s Poultry Science Journal, 51:141-147.

Huyghebaert G. 2007. Trial ILVO Aromabiotic, Internal Report.

Ingram DR, Hatten III LF, Homan KD. 2008. A study on the relationship between eggshell colour and eggshell quality in commercial broiler breeders. International Journal of Poultry Science 7(7):700-703.

Lourens A. 2008. Beschermingsmechanismen van broedeieren tegen pathogenen en de aanwezigheid van de cuticula. Animal Sciences Group, Wageningen UR, rapport 143:Lelystad, The Netherlands.

Mauldin JM. 1994. Reducing contamination of hatching eggs. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 3:234-237.

Roberts JR. 2005. Egg quality guidelines for the Australian egg industry. XIth European Symposium on the quality of eggs and egg products. Doorwerth, The Netherlands.

Solomon SE. 1991. Egg and eggshell Quality. Wolfe Publishing Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

Tona K, Bamelis F, De Ketelaere B, Bruggeman V, Decuypere E. 2002. Effect of induced moulting on albumen quality, hatchability, and chick body weight from broiler breeders. Poultry Science, 81:327-332.

Van de Ven L. 2009. Storage of hatching eggs in the production process. International Hatchery Practice 18(8).