Chickens Open Wide for Gelatin Bead Vaccine

Published: January 23, 2014

By: USDA, Agricultural Research Magazine

Making sure all newborn chicks are vaccinated right out of the hatchery isn’t always easy. Some birds may be missed by standard poultry vaccination methods and, consequently, left with little defense against intestinal diseases. Developed by scientists at the Agricultural Research Service, a new vaccine delivery system to prevent diseases like coccidiosis may be more appetizing to birds than traditional methods.

Coccidiosis, a common and costly poultry disease, is caused by tiny, single-celled parasites. These parasites, which belong to the genusEimeria, live and multiply in the intestinal tract and cause tissue damage that hinders the bird’s ability to digest feed and absorb nutrients. Infected birds shed oocysts—the egglike stage of the parasite—in their feces, and the oocysts transform into infectious forms once in litter, soil, feed, or water. As chickens peck around in the litter, they can ingest the oocysts and become infected. The results are slower weight gain and growth and sometimes death.

The disease costs an estimated $350 million in the United States and more than $3 billion worldwide each year. Until recently, coccidiosis outbreaks were mainly controlled by medicating feed with anticcocidial drugs, but the parasite’s increasing resistance to drugs prompted the development of vaccines.

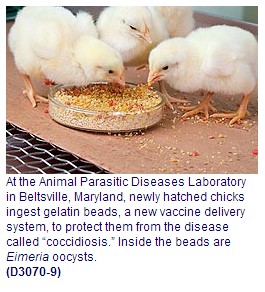

Scientists at ARS’s Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center (BARC) in Beltsville, Maryland, are developing better vaccines and methods of protection against coccidiosis and other poultry diseases. Collaborating with researchers at the nonprofit Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in San Antonio, Texas, they have developed an effective vaccine delivery system by putting low doses of live Eimeria oocysts inside gelatin beads that chickens readily gobble up.

Beads Are Better

Beads Are Better

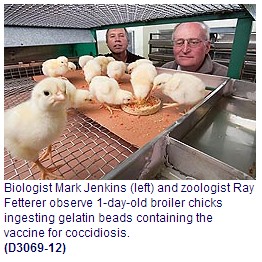

Microbiologist Mark Jenkins and zoologist Ray Fetterer, in BARC’s Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory, are attempting to increase vaccine uptake by studying alternative delivery methods. With the standard industry vaccination method, about 100 chicks at a time are placed into a tray that’s detected by a light sensor as it moves, activating the release of vaccine spray above the heads of the chicks. A harmless red dye in the spray is used to identify birds that have been vaccinated. Chicks inhale or ingest the vaccine, which induces protection against disease.

Jenkins used a hand-held sprayer to deliver a vaccine formulation to newly hatched chicks, and then he measured vaccine uptake.

Jenkins used a hand-held sprayer to deliver a vaccine formulation to newly hatched chicks, and then he measured vaccine uptake.

“With spraying, some chicks were getting a lot of the vaccine and some weren’t getting any,” Jenkins says, leaving them vulnerable to acute coccidiosis and associated necrotic enteritis.

Scientists looked at gelatin beads as an alternative vaccination method. They experimented with different formulations, sizes, and colors. The beads they settled on were red or green and about 2 millimeters in diameter, similar to the size of feed grains fed to young chicks.

“Our primary goal was to develop a formulation that would prevent the gelatin beads from drying out when they’re put into poultry houses, where temperatures can exceed 90°F ,” says Joseph Persyn, SwRI manager of microencapsulation and nanomaterials. “The beads needed to retain moisture to keep the Eimeria oocysts active and to remain pliable so the chicks would eat them.” When beads dry out, they become as hard as pebbles, Persyn adds.

Beads for Broilers

After seeing positive results in chicks of egg-layer hens, Jenkins and Fetterer evaluated the effectiveness of the gelatin bead vaccine in broilers, which are raised for meat.

After seeing positive results in chicks of egg-layer hens, Jenkins and Fetterer evaluated the effectiveness of the gelatin bead vaccine in broilers, which are raised for meat.Vaccine uptake and protection against Eimeria challenge infection was compared between day-old chicks fed gelatin beads, those immunized with a hand-held sprayer, and a control group. Chicks fed gelatin beads had a vaccine uptake 10- to 100-fold greater than the spray-vaccine group. Also, birds that consumed vaccine beads displayed higher and more uniform protection against coccidiosis than spray-vaccinated birds.

“Response was amazing in broilers,” Jenkins says. “You put them in a cage and they run over and start eating right away. Within an hour, those beads were all gone.”

Scientists also examined the efficacy of vaccine beads in chickens raised similarly to those in a poultry house. Newly hatched chicks were vaccinated by either a spray method or gelatin beads. Chicks were then raised in floor-pen cages in direct contact with litter. At 4 weeks of age, all chicks received an experimental challenge dose of Eimeria oocysts. Chicks immunized with beads displayed significantly greater weight gain than an unvaccinated control group. Their ability to convert feed into body mass also was greatly enhanced.

“Gelatin beads may effectively improve vaccine delivery to chickens in the field and thereby reduce the incidence of coccidiosis,” Jenkins says. “This would ultimately improve performance in broilers as well as egg-layers.”

The next step is to test the gelatin beads in a commercial broiler house, Jenkins says. The scientists are looking for a poultry industry partner to take the next step in evaluating the beads.

The collaboration between ARS and SwRI will continue. Research will focus on investigating methods to improve the gelatin bead formulation and the possibility of developing a vaccine delivery device that can be used in commercial poultry houses.

A patent application has been filed by ARS and SwRI scientists for their technology of incorporating Eimeria oocysts into gelatin beads.—By Sandra Avant, Agricultural Research Service Information Staff.

This research is part of Animal Health (#103), an ARS national program described at www.nps.ars.usda.gov.

Mark Jenkins is with the USDA-ARS Animal Parasitic Disease Laboratory, 10300 Baltimore Ave., Beltsville, MD 20705-2350; 301-504-8054.

"Chickens Open Wide for Gelatin Bead Vaccine" was published in the January 2014 issue of Agricultural Researchmagazine.

Source

USDA, Agricultural Research MagazineRecommend

Comment

Share

20 de febrero de 2014

if a chick ingest too many oocysyt that are given in feed then it is going toward out break of disease.if this leads then what precautionary measures are to be taken

Recommend

Reply

6 de febrero de 2014

Sir

It is a good effort and very useful for broiler breeders and commericials also

Recommend

Reply

Would you like to discuss another topic? Create a new post to engage with experts in the community.