I. INTRODUCTION

In Bangladesh, duck flock management is practiced using two systems: viz. stationary and nomadic. ‘Nomadic ducks’ are those which scavenge in post-harvest paddy fields during the day and stay in temporary enclosures or tents overnight near the scavenging area (Henning et al., 2012). Stationary or household ducks are kept overnight near the farmer’s house; they travel only over short distances and are often reared by families in subsistence farming systems (Ghosh et al., 2012). Increased productivity of stationary and nomadic ducks has the potential to reduce malnutrition and increase family income (Pervin et al., 2013).

Duck raising has some benefits over chicken raising: ducks easily adapt to a wide range of environments (Rahman et al., 2009); they lay more eggs and produce more meat than indigenous chickens (Rahman et al., 2007); and women and aged people are able to manage ducks easily. However, there is limited scientific information available regarding the management and health of stationary and nomadic ducks in Bangladesh. This study was undertaken to describe the management and health status of stationary and nomadic ducks in the coastal and Haor areas of Bangladesh.

II. METHODOLOGY

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in stationary and nomadic duck owning households using a structured questionnaire between February and June 2016. Low-lying upazilas (sub-districts) of Chittagong (coastal area) and Moulavibazar (Haor area) districts in Bangladesh were selected for the present study according to the highest density of ducks and availability of water bodies (BBS, 2012). Eight stationary duck households per village across 8 villages in the Chittagong district and four stationary duck households per village across 4 villages in the Moulvibazar Districts were selected; thus a total 80 stationary duck households was involved in this study (64 in Chittagong and 16 in Moulavibazar). In the Moulvibazar district, six households having nomadic duck flocks were selected from the four villages in the Barlekha upazila and four additional households were selected from Vatera from the Kulaura upazila having nomadic duck flocks.

Five interviewers (veterinary students and a researcher from CVASU) were trained in interviewing techniques and conducted the interviews. A questionnaire was developed containing closed and open-ended questions. It explored the flock structure, housing systems, feeding, predation, health care, disease prevention, and vaccination of stationary and nomadic ducks. The questionnaire was pre-tested with 8 stationary and 1 nomadic duck farmers, none of whom were included in the main study. A total of 81 questions was modified following pilot testing, with ambiguous questions being eliminated or modified. Institutional approval for conducting interviews with the stationary and nomadic duck owners was obtained from The University of Queensland, Human Research Ethics Committee (No. 2016000342). Data analysis was conducted in STATA (Stata/SE 14.1, Stata Statistical Software, Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive and summary statistics were produced. Proportions of duck management factors were compared between stationary and nomadic ducks using Fisher’s exact test. A probability value of <0.05 was considered significant.

III. RESULTS

A total of 10 stationary duck flock owners who had no ducks at the time of the interview were excluded from the analysis. Nomadic duck flocks (N=10) were larger than stationary flocks (N=70) with mean (median, range) flock sizes of 6.5 (5, 2-18) and 152.0 (132.5, 65-300), respectively. Indigenous ducks were the most common type of duck in the stationary flocks (95.7%; N=67) and Khaki Campbell was the predominant breed in nomadic flocks (80.0%; N=8). Indian Runner ducks were reared only by the stationary duck farmers (14.0%; N=5). Overall, 75.7% (N=53) of the stationary duck flocks raised ducks together with other poultry, while none of the nomadic flocks had other poultry.

Housing of stationary and nomadic ducks differed considerably. Nomadic ducks were provided with temporary enclosures near the scavenging areas made from fishing nets (100.0%; N=10), while only a few of the stationary flocks use this type of material (14.3%; N=10) (P < 0.001). In general, stationary duck farmers provided solid houses, made from corrugated iron, bamboo, wood, mud or bricks.

Paddy rice was the main feed source for all nomadic ducks (100%; N=10) but not for stationary flocks (11.4%; N=8), while rice polish was the major supplementary feed for stationary ducks (81.4%; N=57) but not for nomadic flocks (30%; N=3). In addition to paddy, the majority of the nomadic farmers (60.0%; N=6), but very few stationary duck farmers (8.6%; N=6) provided commercial feeds for their ducks (P < 0.001). The latter group provided cooked rice (80%), and some rice husk (14.3%), kitchen waste (4.3%), wheat bran (2.0%) and homemade feed (2.0%), whereas none of these were provided to nomadic flocks.

Scavenging food was more abundant in the rainy season (Jun-Aug) for stationary ducks (74.0%; N=52) and in the winter for nomadic ducks (60.0%; N=6). Scavenging feeds for nomadic ducks included more insects (100.0%, N=10), worms (90.0%, N=9) compared to stationary ducks (60.0%, N=42; 50%, N=35), but similar amount of fish and snails (97-100%).

Nomadic flocks were only raised for the production of table eggs whereas hatching egg production was the main reason for keeping stationary ducks (68.6%; N=48) since usually both sexes were present in the flock. All nomadic duck farmers (100.0%; N=10), but only 7.1% of stationary duck farmers (N=5) bought ducklings from government hatcheries (P < 0.001). Purchase of fertile eggs from neighbors to produce ducklings for restocking their own flock was more common in stationary (54.3%; N=38) compared to nomadic flocks (10.0%; N=1) (P = 0.005).

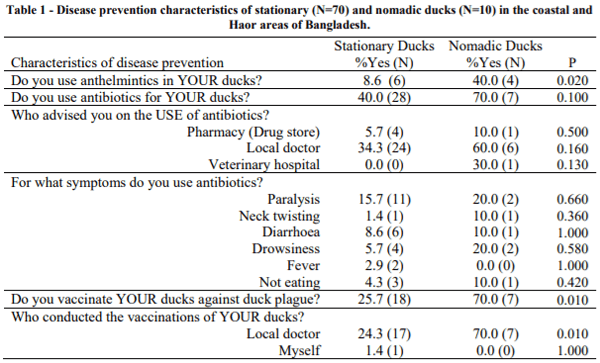

Sudden death of ducks was experienced by all nomadic duck flock owners, but only in 40.0% (N=28) of stationary duck flocks (P < 0.001). Use of anthelmintics was more common in nomadic (40.0%; N=4) compared to stationary duck flocks (8.6%; N=6) (P = 0.018) (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of nomadic duck flock owners vaccinated against duck plague (70.0%; N=7) compared to stationary duck flock owners (25.7%; N=18) (P = 0.009).

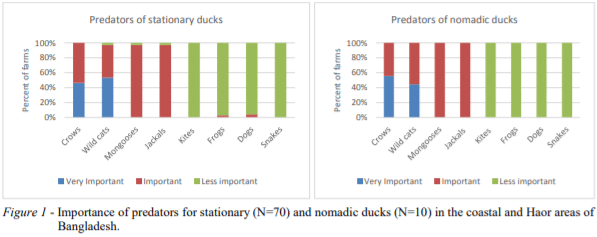

Both stationary and nomadic duck farmers reported the existence of a wide range of predators. Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and a range of wild cat species were the most important predators for both stationary and nomadic duck flocks (Figure 1).

IV. DISCUSSION

The preference of stationary duck farmers for indigenous breeds is due to their belief that these breeds are more resistant to common predators and diseases (Baki et al., 1993) and that these birds are suitable for both egg and meat production. In contrast, nomadic flocks were dominated by the high egg producing Khaki Campbell breed.

Few of the stationary duck farmers (only 8.6%) provided commercial feeds because of their expense making such provision not cost-effective for free range, medium to low egg producing scavenging type of ducks. The stationary duck farmers produced ducklings from hatching eggs of their own stock, instead of buying ducklings from government hatcheries, because it is a general belief that ducklings purchased from hatcheries are less resistant to prevailing duck diseases (Baki et al., 1993). Since nomadic duck farmers rear a large number of ducks, they bought ducklings from hatcheries, mainly through middleman, and ensured that the ducks are vaccinated routinely. Snails and fish were the most abundant scavenging feeds that were available to ducks. In fact, ducks are very good foragers and help control weeds and pests in crop fields (Manda et al., 1993). Young ducklings from hatch to about three weeks of age prefer tadpoles, insects and worms, as they are palatable and a very good source of animal protein, whereas older birds like to seek paddy, shrimps, snails, insects, small fishes and weeds from the field (Nind and Tu, 1998). Scavenging feeds are plentiful during the rainy season (May-July), and scavenging is common for stationary ducks. However, this season is less favorable for nomadic ducks since the Haor areas are flooded and ducks cannot scavenge there. However, late winter is another peak season both for stationary and nomadic ducks. During this time, floodwaters have declined providing a high concentration of worms, insects, snails and fishes (Kabir et al., 2007).

Predator attacks are a major constraint to duck farming in Bangladesh (Hoque et al., 2010). Some predators feed solely on duck eggs, while others target ducklings or adults. Abundance of excessive predators and losses of many young are distressing for duck farmers and farmers often change their management in response to the increased predation risk (Zimmer et al., 2011), such as modifying the duration of scavenging or using different scavenging habitats. However, this sometimes results in a shift to less suitable habitats for nomadic ducks with less access to food (Lima, 1998).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The field work for this research was financially supported by the Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia Research (LANSA) research consortium, and is funded by the UK Department for International Development (DIFID). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK Government's official policies. The authors also thank the farmers, the interviewers and all people involved in the field data collection.

Abstract presented at the 30th Annual Australian Poultry Science Symposium 2019. For information on the latest edition and future events, check out https://www.apss2021.com.au/.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)