Background

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), is one of the biggest threats to food safety and considered a One-Health issue with the potential of spreading to other countries since resistant pathogens do not recognize boundaries [1, 2]. Recently, we have shown the transmission of AMR E. coli among chickens, humans, and the poultry environment [3, 4]. Globally, antimicrobial agents are used in food animal production to ensure good health and productivity of the animals [5–7]. Multiple studies have shown that inappropriate use of these antimicrobial agents in food animal production particularly poultry has led to the development of AMR [8–10].

Commensal E. coli are known to be part of the normal fora of the gastrointestinal tracts of man and animals without causing any harm to their host [11, 12]. Several E. coli strains have been used as indicator organisms in various studies on AMR [11, 13]. Although commensal E. coli are harmless to the host, the bacteria can acquire resistance genes and act as a reservoir for the spread of multidrug resistance (MDR) to and from food to humans [13]. The genetic structure of E. coli strains is usually influenced by several factors including the host and environment enabling the bacteria to acquire various AMR mechanisms [13, 14].

In September 2016, 193 member countries including Nigeria signed the United Nations General Assembly resolution to develop national action plans (NAP) on AMR [15]. In November 2016, Nigeria established its AMR coordinating body at the Nigeria Center for Disease Control (NCDC), and in January 2017, a One-Health AMR Technical working group was inaugurated to conduct AMR situation analysis and develop Nigeria’s NAP [16]. One of the data gaps identified from the AMR situation analysis was the paucity of AMR studies done in Nigeria across humans, food-producing animals, and the environment [16].

It has been documented that the continuous use of antimicrobial agents for therapeutic purposes against infections has led to the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria such as MDR E. coli [17]. MDR bacteria have made it difficult to treat certain infections effectively with modern or conventional antimicrobial agents [18]. AMR has resulted in treatment failure in human and animal populations, because of the emergence of MDR foodborne pathogens like E. coli arising from the abuse or misuse of antimicrobial agents [19]. This scenario further deteriorates in Nigeria because of the increasing number of farmers who practice self-prescription as well as self-administration of antimicrobials to their animals [5, 20]. Poultry farmers have easy access to antimicrobials that are available over-the-counter without prescription [3] and evidence shows that farmers administer the antimicrobials repeatedly against non-responsive infections [20, 21]. These actions by the farmers further promote the emergence and spread of antimicrobial-resistant foodborne pathogens with serious implications on public health [22]. Continuous administration of antimicrobial agents to chickens for prophylaxis, therapeutic, or growth promotion purposes increases the antibiotic selection pressure for resistance in the bacteria [23]. Our recent publication demonstrates that occupational exposure over ten years to chickens on poultry farms or live bird markets (LBMs) was a risk factor for MDR E. coli among poultry workers in Abuja [3].

We hypothesized that chickens harbouring MDR E. coli as well as contaminated poultry farm or LBM environment can become potential sources for transmission of resistance genes to poultry workers exposed to chickens and the environment on poultry farms or markets. To better understand the association between MDR E. coli isolates recovered from humans, chickens and poultry environment, we investigated the genetic relatedness of MDR E. coli isolates from poultry-workers, chickens, and selected poultry farms/LBM environments in Abuja, Nigeria.

Methods

Study overview

Our current study was part of a larger project conducted from December 2018 to February 2020 exploring MDR E. coli in humans, chickens, and the poultry farm/market environment. An aspect of this research exploring the risk factors for MDR E. coli among poultry workers has already been previously published [3].

Characterization of E. coli isolates

Of 429 samples collected in the course of the present study, 110 E. coli strains isolated from the stool of apparently healthy poultry workers, faecal samples obtained from chickens as well as from poultry litter and water obtained from farm and LBM environments were characterized. The sample collection procedures, isolation of E. coli from these samples, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiling of E. coli using the disk diffusion method have been described previously [3]. Briefy, suspected dark pink E. coli colonies on MacConkey agar were streaked on Eosin Methylene Blue agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Isolates were confirmed as E. coli using Microbact GNB 24E (Oxoid, UK).

Genotypic Detection of E. coli isolates

Whole genome sequencing (WGS) of E. coli isolates

All isolates were subjected to WGS as previously described [4]. Briefly, libraries for each E. coli isolates were prepared for WGS using a Nextera XT kit. We processed 0.3 ng/µL of DNA from each isolate using a Nextera XT DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA), pooled together, and sequenced on an Illumina Miseq platform using a 2×250 paired-end approach (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA). Raw sequencing reads were de-multiplexed and converted to fastq files using CLC Genomics workbench version 9.4 (Qiagen bioinformatics, Valencia, CA). The DNA sequences for each isolate were transferred to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database after which each isolate was assigned an accession number.

Bioinformatic analysis of WGS data

Antimicrobial susceptibility determinants of E. coli isolates

High-quality Illumina paired-end reads were assembled de novo into the draft genome sequence for each isolate using SPAdes assembler v.3.13.1 [24]. In silico detection and typing of resistance genes was done using ResFinder 3.2, a Center for Genomics Epidemiology (CGE) bioinformatics tool (database version 2020–02-11), to determine the acquired AMR genes as well as assess chromosomal point mutations [25]. For each isolate, we used between 95–100% identity to match individual genes to an annotated resistance gene. [25]. In silico determination of the existing plasmid replicon types of each E. coli isolate was done by submitting the assembled genomes to PlasmidFinder 2.1, a CGE bioinformatics tool (database version 2020–04-02). The selected threshold for minimum percentage identity was 95% while the minimum coverage of the contig was set at 60% [26]. The in silico plasmid MLST typing of replicons (IncHI2 and IncF) were determined by submitting the assembled genome to pMLST 2.0 (database version: 2020–04-20) bioinformatics tool on the CGE website [26].

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of MDR E. coli isolates

As previously described [4] in silico MLST-analyses of the E. coli isolates were determined using schemes demonstrated by Achtman which made use of allelic variation amongst seven housekeeping genes (adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA) to assign sequence types (STs) [27]. We used whole-genome sequence data to generate the E. coli MLST assignment for each isolate that perfectly matched the alleles in the MLST database. MLST Finder 2.0, a CGE bioinformatics tool was used to assign STs to the isolates with 100% match against known MLST alleles while those without perfect matches were identifed as unknown [28]. Some isolates were assigned as a new type after matching with MLST alleles of unknown ST in the MLST database.

Determination of E. coli Phylogroups, SNPs calling and Phylogeny

Phylogroups of E. coli genomes were determined using an in silico Clermont typing method [29]. The Clermont Typer web interface is hosted by CATIBioMed (IAME UMR 1137) and accessible at http://clermontyping.iameresearch.center/.

Phylogenetic trees were constructed to determine the phylogenetic relatedness of the E. coli isolates using the technique known as SNP calling described by Kaas et al. [30]. Briefy, the tool CSI Phylogeny, a CGE bioinformatics tool accessed online at https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/servi ces/CSIPhylogeny/ was used for SNP calling. The CSI phylogeny uses BWA to map raw reads to a reference sequence and uses Samtools for SNP calling. E. coli strain NCTC11129 was used as the reference strain for SNPs calling to identify variants present in the chromosome of each isolate. The selected thresholds used were: cut-ofs for depth=10x; SNP quality=30; mapping quality=25 and Z score=1.96. The phylogenetic SNP-based maximum likelihood tree were annotated and visualized using the programs Figtree (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/fgtree/) and interactive Tree of Life tool—iTOL (http:// itol.embl.de/itol.cgi). Pairwise SNP differences between genomes were computed to determine if isolates of different origins were related.

Data analyses

Antimicrobial susceptibility data were analyzed using Epi Info 7 software by computing frequencies and proportions. The 108 assembled E. coli genomes of the present study have been deposited by the Takur Molecular Epidemiology Laboratory, NC State University (GenomeTrakr Project) in the NCBI database under the Bioproject ID number PRJNA293225. The remaining two isolates have accession obtained from the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) as previously reported [4].

Results

Antimicrobial susceptibility profle of E. coli isolates

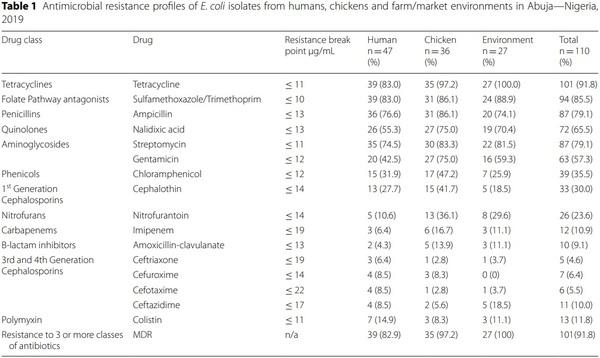

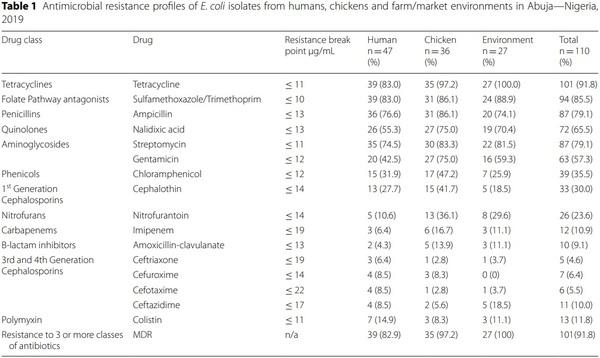

A total of 110 E. coli strains were isolated from 122 human stool samples obtained from poultry workers on farms and LBMs; 111 faecal samples obtained from chickens on farms and LBMs; and 196 poultry litter and water samples obtained from farm and LBM environments. Of the 110 E. coli strains 42.7% (n = 47) were recovered from humans; 37.7% (n = 36) from chickens and 24.5% (n = 27) from poultry environment. High resistance rates were observed for tetracycline, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, streptomycin, ampicillin, nalidixic acid and gentamicin. On the contrary resistance to colistin, imipenem, ceftazidime, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefuroxime, cefotaxime and ceftriaxone were quite low although colistin resistance rate of 11.8% in commensal E. coli is quite worrisome (Table 1).

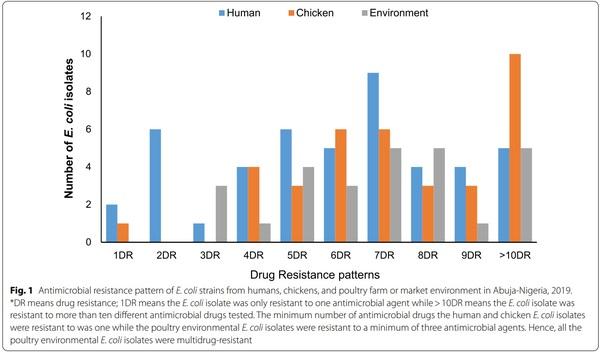

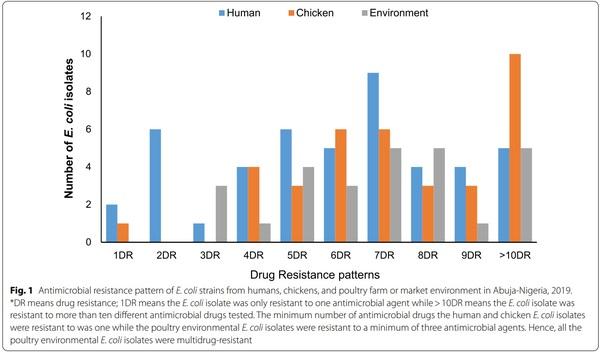

Analysis of resistance profiles of the 110 isolates showed that a single isolate (0.9%) from a poultry farmer was susceptible to all antimicrobial drugs tested; 4 (3.6%) were resistant to only one antimicrobial drug, 4 (3.6%) were resistant to two antimicrobial drugs and interestingly 101 (91.8%) were MDR (resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobial drugs). The number of antimicrobials against which each isolate showed resistance was between one and thirteen. Surprisingly, a single isolate from a poultry farm was resistant to 13 out of 16 antimicrobials tested. The AMR phenotypes with AMP, CEP, CHL, CT, GEN, NAL, S, SXT, and TET profile had the highest frequency of 13.6% (n = 15). Figure 1 summarizes the multiple AMR patterns exhibited by the isolates.

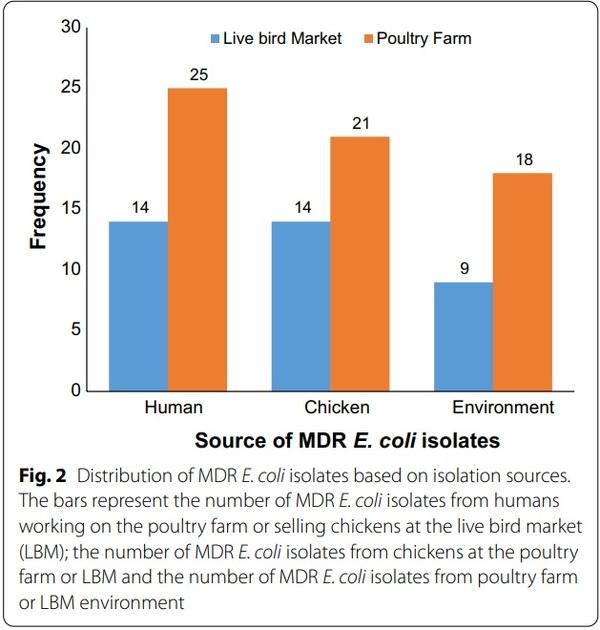

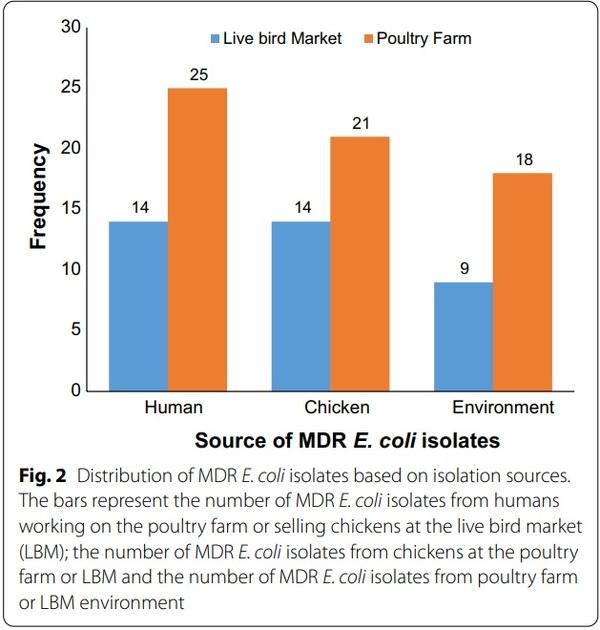

Prevalence of MDR E. coli in humans, chickens and poultry farm/LBM environment

The overall prevalence of E. coli from all sources was 26.8% (n=115), however, only 110 were further characterized due to viability as the remaining five isolates were mistakenly discarded. Of the 110 E. coli isolates, 91.8% (n=101) were MDR E. coli. Of these MDR E. coli isolates 38.6% (n=39), 34.7% (n=35), and 26.7% (n=27) were recovered from humans, chickens and poultry environment respectively (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, all the poultry environment isolates were MDR. Of the 101 MDR E. coli isolates 47.5% (n=48) were MDR5 (resistant to more than 5 classes) and 38.6% (n=39) were classified as XDR (resistant to 8 or more classes i.e. extensively drug-resistant isolates). Overall, 36.6% (n=37) of the isolates originated from the LBMs while 63.4% (n=64) originated from farms. Of the 39 XDR E. coli isolates 41% (n=16), 33.3% (n=13), and 25.6% (n=10) were recovered from chickens, humans and the poultry environment respectively.

In silico AMR gene analysis of MDR E. coli isolates in humans, chickens and poultry environment

This study identified 57 different resistance determinants from 101 MDR E. coli isolates. Genes encoding resistance to aminoglycosides accounted for the majority with about 14 different determinants (aadA1,

(70.3%) of aph(6)-Id, which is a plasmid-encoded gene, was also observed. About two-thirds of the isolates (67.3%) exhibited aph(3)-Ib gene, a metabolic enzyme that confers aminoglycoside resistance. The aac(3)-IId gene responsible for conferring gentamicin resistance was observed in 27.7% of the MDR E. coli isolates. We also detected aac(6)-Ib-cr gene, responsible for the reduction in ciprofoxacin activity in two MDR E. coli isolates. Six different variants of β-lactam resistance genes were detected (blaTEM-1, blaOXA-1, blaOXA-10, blaOXA-129, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTXM-65) out of which blaCTX-M type was classical of the ESBL producing E. coli. Ten diferent fuoroquinolone resistance determinants were observed, an important antimicrobial on the WHO list, (qnrB1, qnrB19, qnrB52, qnrS1, qnrS2, qnrS3, qnrS7, qnrS11, qnrS13, aac(6)-Ib-cr) and associated with mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE genes. We detected other important resistance determinants such as trimethoprim resistance (dfrA1, dfrA8, dfrA12, dfrA14, dfrA15, dfrA17, dfrA21, and dfrA27), macrolide resistance (mdfA, mphA, mefB, ermB, ereA, mphE and msrE), phenicol resistance (cmlA1, catA1, catA2, catB3, foR), rifampicin resistance (ARR-2 and ARR-3), sulphonamide resistance (sul1, sul2, sul3), tetracycline resistance (tetA, tetB, tetM) and plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene (PMCR)—mcr-1.1.

Multi‑locus sequence determination of MDR E. coli isolates

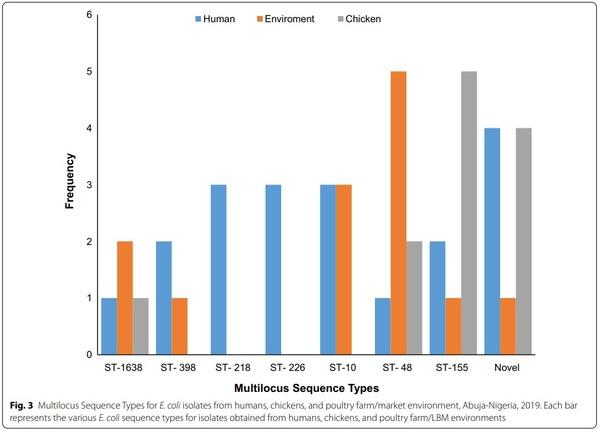

The 101 MDR E. coli isolates belonged to 66 diferent sequence types (ST), out of which one (1) was non-conclusive and eight (8) were new types. In the in silico MLST analysis of E. coli isolates, the following were observed to appear more than once: ST155 (7.9%; n=8), ST48 (7.9%; n=8), ST10 (5.9%; n=6), ST1638 (4%; n=4), ST398 (3%; n=3), ST216 (3%; n=3), ST226 (3%; n=3), ST101 (2%; n=2), ST117 (2%; n=2), ST165 (2%; n=2), ST206 (2%; n=2), ST4663 (2%; n=2), ST1286 (2%; n=2), and ST1196 (2%; n=2). The most prevalent STs are shown in Fig. 3.

Phylogroups of E. coli isolates from humans, chickens and poultry environment

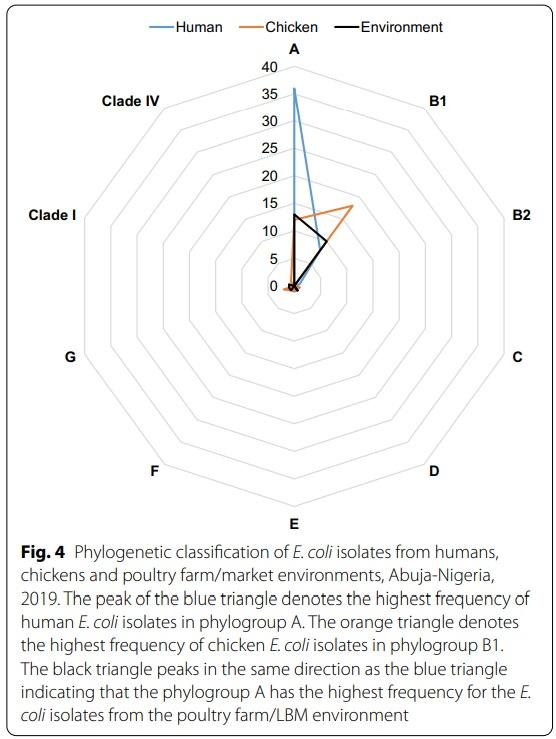

A majority of the isolates belonged to phylogroup A (n=61, 55.5%) followed by phylogroup B1 (n=36, 32.7%) while the rest belonged to phylogroup G (n=3, 2.7%); D (n=2, 1.8%); E (n=2, 1.8%); F (n=2, 1.8%); B2 (n=1, 0.9%); C (n=1, 0.9%); clade I (n=1, 0.9%) and clade IV (n=1, 0.9%). Isolates with phylogroup A originated from workers (n=36) and poultry environment (n=13) while isolates recovered from chickens mostly belonged to phylogroup B1 (Fig. 4). Of the 36 E. coli isolates, belonging to phylogroup B1, 22.2% (n=8); 50% (n=18) and 27.8% (n=10) were recovered from humans, chickens and the poultry environment respectively.

All isolates assigned ST10 (n=6), ST218 (n=3), ST398 (n=3) and ST1638 (n=4) belonged to phylogroup A. However, all but one isolate assigned ST48 (7/8) and ST226 (2/3) also belonged to phylogroup A while a majority with ST155 (7/8) and novel ST (5/8) belonged to phylogroup B1.

Plasmid replicon profiles of MDR E. coli isolates from humans, chickens and poultry environment

Forty (40) diferent plasmid replicon types were detected among 97 MDR E. coli isolates however, 4% (n=4) did not harbour any plasmid replicons. The most prevalent plasmid replicons detected in descending order were p0111 (36.6%, n=37); IncFIB(AP001918) (33.7%, n=34); IncFII (18.8%, n=19); ColpHAD28 (14.9%, n=15); IncQ1 (13.9%, n=14); IncFIB(K) (13.9%, n=14); ColpVC (12.9%, n=13); IncFIC(FII) (12.9%, n=13); IncR (9.9%,

n=10); IncFII(pCoo) (9.9%, n=10); IncY (9.9%, n=10); IncX1 (8.9%, n=9) and IncI1-I(gamma) (8.9%, n=9). The plasmid replicons recovered from human isolates were more genetically diverse than those recovered from chickens and the poultry environment. Eighteen replicon types were common to isolates from all sources: p0111, IncFIB(AP001918), IncFII, ColpHAD28, IncQ1, IncFIB(K), ColpVC, IncFIC(FII), IncX1, IncFII(pCoo), IncI1-I (gamma), IncFII (29), IncFII(pHN7A8), IncFIA, Col156, IncHI2, IncHI2A and IncX4.

IncFIB(AP001918) was the most common among human isolates (n=12) while p0111 was commonly detected in both chicken (n=15) and poultry environment isolates (n=14). Interestingly, IncFIB (pLF82), a phage plasmid was detected in one isolate recovered from the LBM environment. Eight diferent plasmids were observed to harbour AMR genes. The following AMR genes were carried on plasmid replicons: mcr-1.1+IncX4 (n=2); tetA+IncX1 (n=1); qnrB19+Col440I (n=7); sul2+IncQ1 (n=5); aph(3)-Ib+IncQ1 (n=1); blaTEM-1+IncFIC(FII) (n=1); mdf(A)+IncFIB (n=1); qnrS13+IncFII (n=1) and aac(3)-IIa+IncHI1B (n=1). The plasmid replicons harbouring the AMR genes was commonly detected in commensal E. coli isolates recovered from poultry workers, chickens and the poultry environment.

Determination of pMLST for IncHI2 and IncF plasmid replicons

In silico pMLST identification and typing of IncHI2 and IncF plasmid replicons, were based on the combination of the alleles identified for the genes. For the IncHI2 the assigned ST was ST4 for isolates (MA_251 and MA_252) originating from a poultry farmworker and poultry litter on the same farm. The pMLST analysis assigned the two IncF plasmids for isolates MA_251 and MA_252 with ST[F18:A-B1]. It is interesting to note that although the plasmid structures of the two isolates were so similar, there was no clonal relationship between them.

Phylogenetic analysis of E. coli isolates from humans, chickens and poultry environments

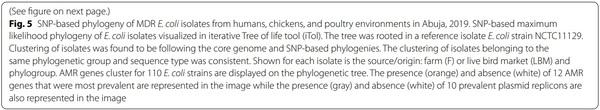

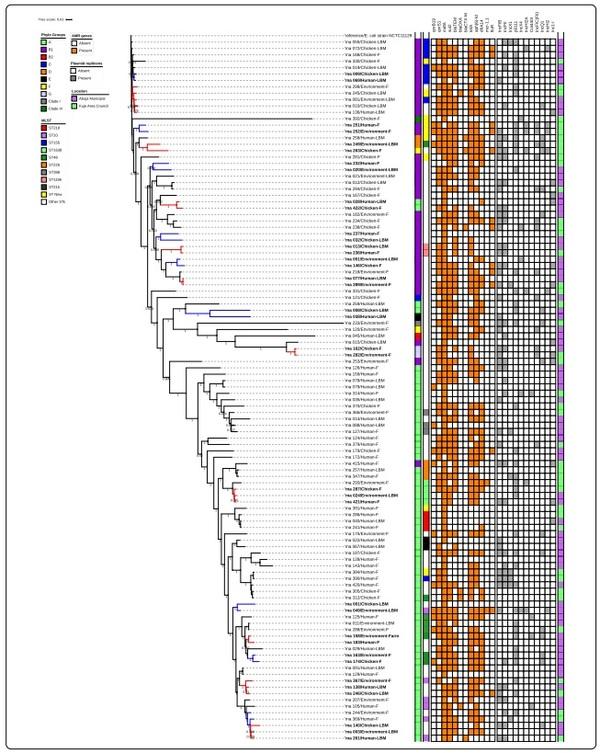

All isolates assigned a phylogenetic group and ST were used to construct phylogenetic trees to determine if the isolates were genetically related or very diverse. Tree phylogenetic trees were constructed: one for all the isolates (Fig. 5), one focusing on isolates with novel STs (Fig. 6a) and one with isolates of different origins assigned the same ST (Fig. 6b).

Overall, 110 isolates used to construct a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showed that the isolates were genetically diverse. The isolates were grouped based on similarities among them. Whole-genome (wg) SNPsbased phylogenetic analysis showed that some isolates sharing the same ST and phylogroups were not clonally related. The strains were in completely different clades in the SNP tree, separated by strains belonging to other STs. Tree isolates with ST-1638 recovered from human, chicken and poultry environment were clustered together on the same clade. Pairwise SNP differences between the

genomes of the isolates showed that they were not clonally related (Fig. 6b).

Two isolates of human and environmental origin with SNPs difference of 6161 were not clonally related although the isolates shared a novel ST and belonged to phylogroup B1 (Fig. 6a). The two isolates originating from the same farm had similar AMR gene profile (qnrB19, qnrS1, mdfA, mefB, sul 2, sul 3, blaTEM1, tetA, tetM, foR); as well as plasmid replicons (p0111, IncFIC(FII), IncHI2A, IncHI2, Col(pHAD28).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the frst study to investigate the prevalence of MDR E. coli in poultry workers, chickens, and the poultry farm/market environments in Nigeria.

The first objective of this study was to characterize E. coli from poultry workers, chickens, and poultry environments. The unhygienic LBM environment where these chickens are sold acts as a reservoir of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and eventually poses a health risk to people working in such an environment. A similar study done in the Netherlands reported a lower prevalence of MDR E. coli in chickens (23%) and chicken farmers (22%) when compared with the present study where a prevalence of 34.7% and 38.6% was detected in chickens and poultry workers respectively [31]. Access to antimicrobials is better regulated in the Netherlands as well as the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programs when compared to Nigeria and could explain the differences observed in both studies. A related study conducted in Bangladesh among poultry and poultry environment reported a much higher prevalence of E. coli (82%) from chicken faecal samples when compared with the findings from this study, with a much lower prevalence of 32.2% [32]. Two similar studies performed among chickens from poultry farms in northern Nigeria also reported a much higher E. coli prevalence of 67.7% [33] and 69.8% [34] from cloacal swabs obtained from chickens on the farm. A possible explanation for the difference between studies carried out in northern Nigeria and our study could be due to the sample types collected as our study isolated E. coli from freshly dropped chicken faecal samples as opposed to cloacal swabs. A study conducted in Pakistan, reported a slightly higher E. coli prevalence of 36% from the poultry farm environment when compared to 26.1% obtained from the poultry environment in the present study [35]. Our study findings are consistent with the reports of a related study carried out in Egypt where E. coli prevalence of 26.8% was obtained from the poultry environment [36]. The similarity observed between our study findings and that of the Egyptian study may be due to similarities in poultry farming practices.

Our study examined AMR in E. coli isolates from poultry farm workers and chicken sellers and compared them to resistance rates of E. coli isolates from chickens and poultry farm/market environment. The patterns of resistance were similar for human and chicken isolates. High resistance rates were observed in isolates recovered from humans, chickens, and poultry farm/market environments for tetracycline, trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, and streptomycin. This is in agreement with the findings of a study conducted in southwest Nigeria, where high resistance rates of E. coli isolates to beta-lactams, tetracyclines, macrolides, and sulfonamides were reported [37]. This finding is not surprising as these antimicrobials are easily accessible and commonly used in poultry production in Nigeria for therapeutic purposes especially in the absence of antimicrobial stewardship programs [38].

Our study revealed a very high proportion (91.8%) of MDR E. coli isolates from all the sources. Interestingly, 83% of human, 97% of chicken, and 100% of poultry environment isolates were MDR E. coli. A possible explanation for this very high level of resistance observed could be because of the lack of prudent use of antimicrobials and the required regulation to support it resulting in over-the-counter availability often without prescription as reported in many studies [16, 38–40]. The potential transmission of the drug-resistant strains between different hosts could also be responsible for this observation because E. coli is a known zoonotic bacteria [13].

The most common beta-lactamase gene observed in this study was the blaTEM-1 gene, which confers ampicillin resistance in E. coli isolates and is in agreement with a previous study that reported ampicillin-resistant E. coli isolates in food, humans, and healthy animals [41]. Our study however, did not detect any genes encoding carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzymes in any of the isolates although phenotypic characterization showed that 10.9% of the isolates were carbapenemresistant. This may possibly be as a result of borderline interpretation of breakpoint settings between resistance and susceptibility. The present study identified one of the most important AMR genes [42], being the PMCR gene—mcr 1.1 harboured on IncX4 plasmids in two isolates recovered from the poultry environment. Evidence shows that the IncX4 plasmids harbouring mcr-1 genes have been detected in human and animal E. coli isolates however, our study recovered these plasmids from the poultry environment [43]. Another study conducted in China also detected PMCR genes—mcr 1 in E. coli isolates sourced from the aquatic environment [44] however, the mcr 3.1 gene was detected in a human Salmonella case in the US [45]. This further buttresses that mcr gene has spread across multiple pathogens. Our study highlights that poultry workers, chickens, and the poultry environments share identical plasmid replicons and this is consistent with the literature [46, 47]. Te IncF plasmids reported as one of the epidemic plasmids were observed in humans, chickens, and the poultry environments to harbour diferent AMR genes; blaTEM-1, mdf(A) and qnrS13 in the present study and these are consistent with the literature [43]. The IncQ1 plasmids were detected in isolates with ST48 recovered from chickens and poultry farm environments harbouring the sul2 genes that confer sulphonamide resistance and this is consistent with reports of other studies [43, 48]. The poor biosecurity measures, unhygienic practices in poultry farms and LBMs, and occupational exposure of over ten years are factors that predispose these humans to get infected with these drug-resistant bacterial strains [3].

To determine the genetic relatedness of the isolates, we analyzed by WGS, E. coli recovered from humans, chickens, and poultry environments. Our results revealed that these isolates showed very diverse genetic profiles. Common STs were assigned based on MLST including ST155, ST48, ST10, ST1638, and ST398 in isolates from humans, chickens, and poultry environments, although ST155 was mostly detected in isolates of poultry origin at the LBM. The most common ST detected among isolates recovered from the poultry farm environment was ST48. Previous studies have reported that E. coli with ST48 in phylogroup A has been detected in healthy volunteers, seafood, and water [49–51]. Our study detected ST48 in E. coli recovered from healthy people, chickens, and the poultry environment. E. coli strains with ST10 have previously been reported as being emerging and pathogenic as implicated in human infections although MDR strains with ST10 have also been detected in poultry and other animal sources [52]. Our study detected MDR E. coli strains with ST10 in healthy individuals, poultry manure, and water. A possible explanation could be that this is becoming an emerging public health issue arising due to possible mutations in the bacteria.

The majority of E. coli isolates in this present study belonged to phylogroup A (55.5%) and phylogroup B1 (32.7%). Most human and poultry environment isolates belonged to phylogroup A while majority of the chicken isolates belonged to phylogroup B1. Our study findings are in agreement with the results of a similar study conducted in Pakistan that reported that phylogroups B1 and A were the most prevalent detected among human and animal E. coli isolates [53]. Interestingly, a study carried out in south-west Nigeria reported that chicken E. coli isolates were evenly distributed into phylogroups A and B1 while phylogroup B1 was the most prevalent among human isolates [37]. Previous studies also showed that E. coli isolates belonging to phylogroup B2 are usually the most virulent, hence MDR [54–56]. However, our study observed that majority of the isolates, which belonged to either phylogroups A, and B1 were MDR. This is consistent with findings from a similar study conducted in south-west Nigeria which reported that isolates belonging to phylogroups B1 and A were MDR [37]. Our study findings are not surprising and consistent with the literature that most commensal E. coli belong to phylogenetic groups A and B1 [57, 58]. However, it is worrisome that these indicator bacteria have become MDR with a negative impact on public health since they could be transferred to more virulent strains or species thus causing disease.

The phylogenetic SNP tree rooted using NCTC11129 reference strain revealed that the isolates were genetically diverse among the identified STs. Two unrelated isolates of human and environmental origin belonging to phylogroup B1 and sharing a novel ST, had Col440I replicons harbouring the qnrB19 genes that confer quinolone resistance and consistent with the literature [43]. In silico pMLST typing of the two isolates further confirmed that the isolates shared the same plasmids: IncHI2[ST-4] and IncF[ST-F18:A-:B1]. Te two isolates although not clonally related, shared the same plasmids (Col440I) harbouring AMR genes (qnrB19) possibly due to horizontal gene transfer. Studies have shown that the IncF and IncHI2 plasmids mainly found in E. coli strains, are frequently detected in humans and animals serving as reservoirs for the spread of AMR genes and have been associated with MDR E. coli [43, 59]. This evidence supports our study results and explanation of a possibility of horizontal gene transfer of AMR genes harboured in the plasmids. Our study did not find evidence of the clonal spread of MDR E. coli at the human-animal-environment interface; however, our findings suggest that mobile genetic elements may have facilitated the horizontal transfer of MDR genes between the plasmids among commensal E. coli which could potentially mutate into real pathogens with serious public health implications [47].

Conclusion

MDR E.coli isolates were found to be prevalent amongst poultry workers, chickens, and poultry farm/market environments in Abuja, Nigeria. The highest resistance rates among MDR E. coli isolates were observed to tetracycline, sulphonamides, penicillins, aminoglycosides, and quinolones which are classes of antimicrobials commonly used in poultry production for treating avian diseases in Abuja. ST-155, ST-48, and ST-1638 were the only STs detected in humans, chickens, and poultry farm/LBM environments in our study. Our findings showed the emergence and spread of MDR E. coli with novel-ST from a poultry farm environment to a poultry farmer, which may have resulted from horizontal transfer of AMR genes harboured in plasmids. Consequent upon these, healthcare and poultry workers should be educated on the fact that people in proximity with poultry are a high-risk group for faecal carriage of MDR E. coli. Competent authorities should enforce AMR regulation to ensure prudent use of antimicrobials to limit the risk of transmission along the food chain and to poultry workers. Farmers should be discouraged from indiscriminate use of antimicrobials in poultry production and encouraged to adopt preventive measures by observing biosecurity as well as good management practices on their farms.

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)