Biosynthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles from Marine Seaweed Colpomenia Sinuosa and its Antifungal Efficacy

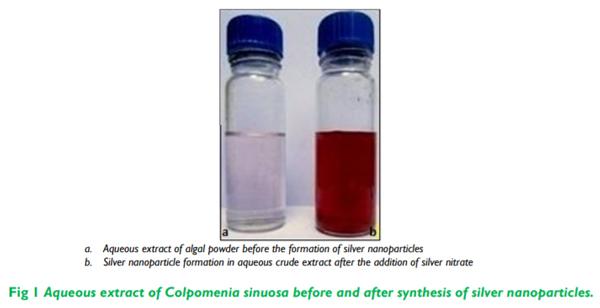

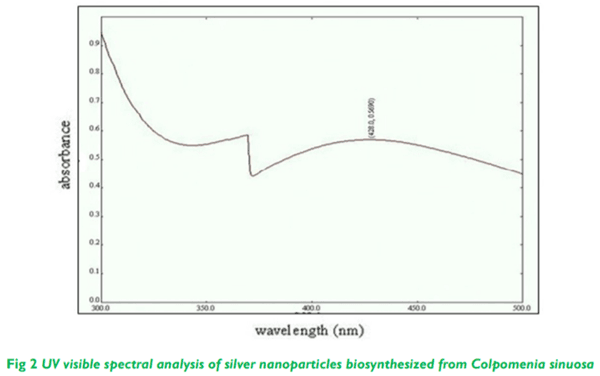

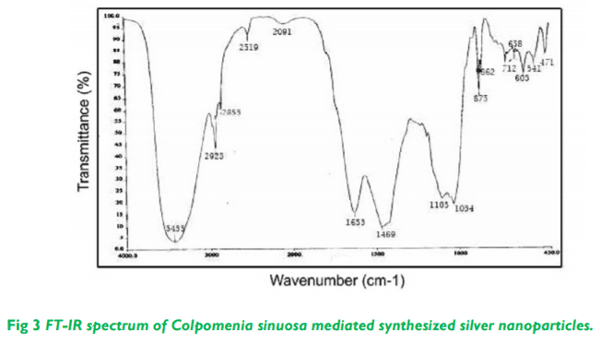

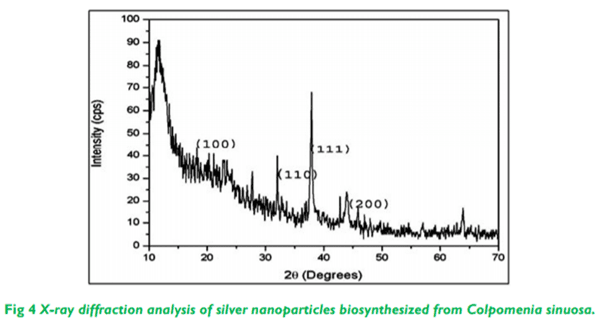

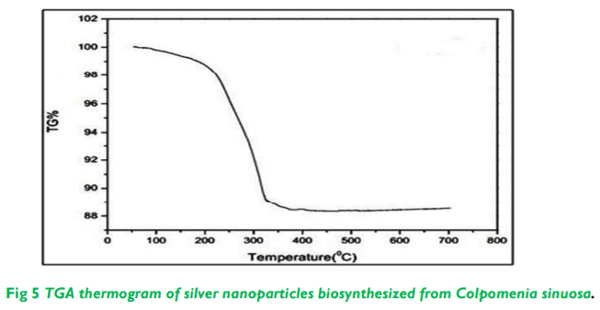

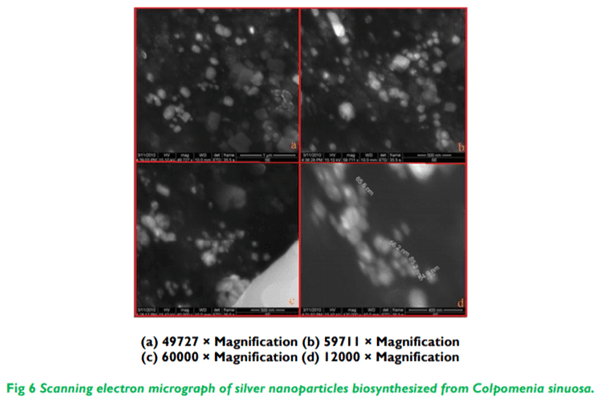

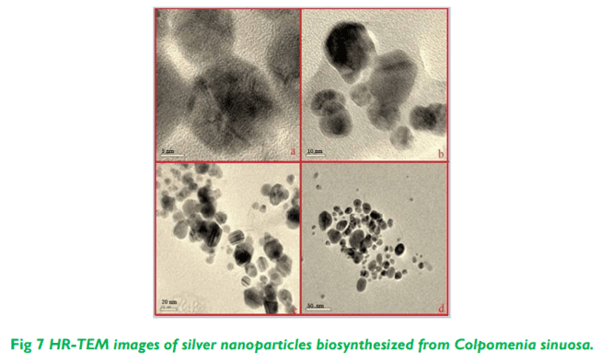

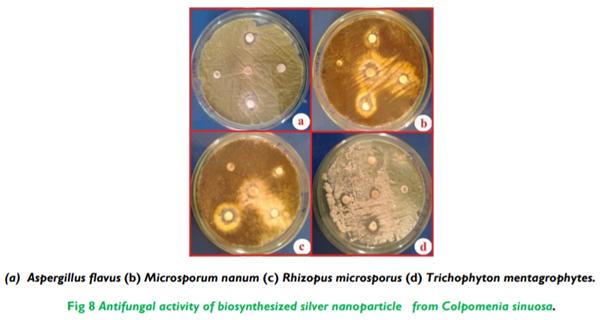

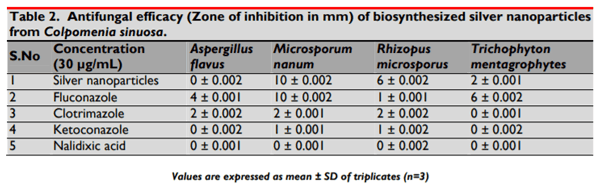

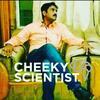

The present study illustrates the biosynthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) from marine seaweed Colpomenia sinuosa and their antifungal efficacy was determined against dermatophytic and non-dermatophytic fungi. The dermatophytic fungi used in this study are Microsporum nanum (ATCC 28951) and Trichophyton mentagrophytes (ATCC 28185) whereas the non dermatophytic fungi Aspergillus flavus (ATCC 20048) and Rhizopus microsporus (ATCC 22960). The rich content of phytochemicals, bioactive compounds and secondary metabolites in marine seaweed Colpomenia sinuosa possess the reducing/capping agents that may be environmentally acceptable and eco-friendly for the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. The efficacy of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles from marine macroscopic brown alga was performed using Kirby Bauer Method and the silver nanoparticles biosynthesized was characterized by UV-vis spectroscopy, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy, X-ray Diffraction (XRD) and Thermo gravimetric analysis. Particle size distribution and morphology were investigated by scanning electron microscope which showed silver nanoparticles in the size range of 54-85 nm. The average size of the silver nanoparticle indicated by TEM analysis was found to be 34 nm. The antifungal efficacy of silver nanoparticles at the concentration 30 µg/mL revealed greater efficacy in dermatophytic fungi while Rhizopus microsporus as non dermatophytic fungus showed better antifungal activity when compared to the standard fungal antibiotics used.

Keywords: AgNps, biosynthesis, Colpomenia sinuosa, antifungal efficacy, dermatophytes, non dermatophytes.

1. Singh M, Manikandan S, Kumaraguru AK. Nanoparticles: A new technology with wide applications. Res. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011; 1:1- 11. DOI: 10.3923/rjnn.2011.1.11

2. West JL Halas NJ. Engineered nanomaterials for biophotonics applications: Improving sensing, imaging, and therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2003; 5: 285-292. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.5.011303.120723

3. Paciotti GF, Myer L, Weinreich D, Goia D, Pavel N, McLaughlin RE, et al. Colloidal gold: A novel nanoparticle vector for tumour directed drug delivery. Drug. Delivery. 2004; 11: 169-183. DOI: 10.1080/10717540490433895

4. Jain KK. Nanotechnology-based drug delivery for cancer. Technol. Cancer. Res. Treat. 2005; 4: 407-416. DOI: 10.1177/153303460500400408

5. Wu X, Liu H, Liu J, Haley KN, Treadway JA, Larson JP, et al. Immuno fluorescent labeling of cancer marker Her2 and other cellular targets with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003; 21(1): 41-

6. DOI: 10.1038/nbt764 6. Chan WCW, Maxwell DJ, Gao X, Bailey RE, Han M, Nie S. Luminescent quantum dots for multiplexed biological detection and imaging. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002; 13 (1): 40-6. DOI: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00282-3

7. Sokolov K, Follen M, Aaron J, Pavlova I, Malpica A, Lotan R, et al. Real-time vital optical imaging of precancerous drugs using anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles. Cancer. Research. 2003; 63: 1999-2004. Available from; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12727808

8. Alivisatos AP. The use of nanocrystals in biological detection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004; 22 (1): 47-52. DOI: 10.1038/nbt927

9. Hirsch LR, Stafford RJ, Bankson JA, Sershen SR, Rivera B, Price RE, et al. Nano shell-mediated near-infrared thermal therapy of tumours under magnetic resonance guidance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003; 100 (23): 13549-54. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2232479100

10. Barwal I, Ranjan P, Kateriya S, Yadav SC. Cellular oxido-reductive proteins of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii control the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles. J.Nanobiotech. 2011; 9:56. DOI: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-56

11. Taleb A, Petit C, Pileni MP. Optical properties of selfassembled 2D and 3D super lattices of silver nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998; 102 (12): 2214- 2220. DOI: 10.1021/jp972807s

12. Thirumalai AV, Prabhu D, Soniya M. Stable silver nano particle synthesizing methods and its applications. J. Bio sci. Res. 2010; 1 (4): 259-270. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281282881_ Silver_nanoparticles_synthesis_medical_application_a nd_toxicity_effects

13. Balantrapu K, Goia D. Silver nanoparticles for printable electronics and biological applications. J. Mater. Res. 2009; 24 (9): 2828-2836. DOI: 10.1557/jmr.2009.0336

14. Tripathi RM, Saxena A, Gupta N, Kapoor H, Singh RP. High antibacterial activity of silver nanoballs against E.coli MTCC 1302, S.typhimurium MTCC 1254, B.subtilis MTCC 1133 and P.aeruginosa MTCC 2295. Dig. J. Nanomater. Bios. 2010: 5 (2): 323- 330. Available from: http://chalcogen.ro/323_Tripathi.pdf

15. Patakfalvi R, Dekany I. Preparation of silver nanoparticles in liquid crystalline systems. Colloid. Polym. Sci. 2010; 280 (5): 461- 470. DOI: 10.1007/s00396-001-0629-0

16. Rodriguez SL, Blanco MC, Lopez QMA. Electrochemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000; 104: 9683- 9688. DOI: 10.1021/jp001761r

17. Jeong SH, Yeo SY, Yi SC. The effect of filler particle size on the antibacterial properties of compounded polymer/silver fibers. J. Mater. Sci. 2005; 40: 5407- 5411. DOI: 10.1007/s10853-005-4339-8

18. Shrivastava S, Bera T, Roy A, Singh G, Ramachandrarao, Pand DD. Characterization of enhanced antibacterial effects of novel silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2007; 18 (22): 225- 103. DOI: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/22/225103

19. Bharathiraja S, Suriya J, Sekar V, Rajasekaran R. Biomimetic of silver nanoparticles by Ulva lactuca seaweed and evaluation of its antibacterial activity. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2012; 4(3): 139-143. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289066797

20. Shiny PJ, Mukherjee A, Chandrasekaran, N. Marine algae mediated synthesis of the silver nanoparticles and its antibacterial efficiency. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2013; 5 (2): 239-241. Available from: https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/1517 97/16/16_publications.pdf

21. Mohandass C, Vijayaraj AS, Raja sabapathy R, Satheesh babu S, Rao SV, Shiva, et al. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine seaweed Sargassum cinereum and their antibacterial activity. Ind. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013; 75 (5): 606-610. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC387752 5/

22. Manal AA, Awatif AH, Khalid MO, Dalia FAE, Abdelelah AGA. Silver nanoparticles are biogenic synthesized using an orange peel extract and their use as an antibacterial agent. Intl. J. phys.ical sci. 2014; 9: 34-40. DOI: 10.5897IJPS2013.4080

23. Vishnu Kiran M, Murugesan S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from marine alga Halymenia poryphyroides and its antibacterial efficacy. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2014; 3 (4): 96-103. Available from: https://www.ijcmas.com/Archives-17.php

24. Niemeyer CM. Nanoparticles, Proteins, and Nucleic Acids: Biotechnology Meets Materials Science. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001; 40: 4128-4158. DOI: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011119)40:22<4128::AIDANIE4128>3.0.CO;2-S.

25. Mishra VK, Temelli PF, Ooraikul Shacklock, Craigie JS. Lipids of the Red Alga, Palmaria palmate. Bot. Mari.1993; 36 (2): 169-174. DOI: 10.1515/botm.1993.36.2.169

26. Ajit KA, Meena K, Rao MM, Panda P, Mangal AK, Reddy, G et al. Marine algae: An Introduction, Food value and Medicinal uses. J. Pharm. Res.. 2011; 4 (1): 123-127.

27. Smit AJ. Medicinal and pharmaceutical uses of seaweed natural products: A review. J. App. Phycol. 2004; 16: 245–262. DOI: 10.1023/B:JAPH.0000047783.36600.ef

28. Wong KH, Cheung, PCK. Nutritional evaluation of some subtropical red and green seaweed. Part Iproximate composition, amino acid profiles and some physico-chemical properties. Food. Chem. 2000; 71: 475-482. DOI: 10.1016/s0308-8146(00)00175-8

29. Norziah MH, Ching Ch Y. Nutritional composition of edible seaweeds Gracilaria changgi. Food. Chem.. 2002; 68: 69-76. DOI: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00161-2

30. Ravi S, Baghel, Puja K, Reddy, CRK, Bhavanath J. Growth, pigments, and biochemical composition of marine red alga Gracilaria crassa. J. App. Phycol. 2014; 26 (5): 2143–2150. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267042453

31. Dawes CJ, Kovach C, Friedlander M. Exposure of Gracilaria to various environmental conditions II. The effect on fatty acid composition. Bot. Mari.. 1993; 36: 289-296. DOI: 10.1515/botm.1993.36.4.283

32. Kaehler S, Kennish R. Summer and winter comparisons in the nutritional value of marine macro algae from Hong Kong. Bot. Mari. 1996; 39: 11-17. DOI: 10.1515/botm.1996.39.1-6.11

33. Sokolova EV, Barabanova AO, Homenko VA, Soloveva TF, Bogdanovich RN, Yermak IM. In vitro and ex vivo studies of antioxidant activity of carrageenans, sulfated polysaccharides from red algae. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2011; 150: 426-428. DOI: 10.1007/s10517-011-1159-5

34. Chandini SK, Ganesan PV, Suresh N, Bhaskar. Seaweeds as a source of nutritionally beneficial compounds – A review. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2008; 45: 1–13. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298525973

35. Kladi M, Vagias C, Roussis V. Volatile halogenated metabolites from red algae. Phytochem. Rev. 2004; 3: 337-366. DOI: 10.1007/s11101-004-4155-9

36. Kashman Y, Rudi A. On the biosynthesis of marine isoprenoids. Phytochem. Rev. 2004; 3: 309-323. DOI: 10.1007/s11101-004-8062-x

37. Plaza M, Cifuentes A, Ibanez E. In the search of new functional food ingredients from algae. Trends. Food. Sci. Tech. 2008; 19: 31-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.07.012

38. Holdt SL, Kraan S. Bioactive compounds in seaweed: Functional food applications and legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011; 23: 543-597.

39. Faulkner DJ. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002; 19: 1-49. DOI: 10.1039/B009029H

40. Mirmirani P, Hessol NA, Maurer TA, Berger TG, Nguyen P, Khalsa A. Prevalence and predictors of skin disease in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001; 44: 785- 788. DOI: 10.1067/mjd.2001.112350

41. Kim KJ, Woo SS, Seok KM, Jong SC, Jong GK, Dong GL. Antifungal Effect of Silver Nanoparticles on Dermatophytes. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008; 18 (8): 1482–1484. Available from: http://europepmc.org/article/med/18756112

42. Nasrollahi KH, Pourshamsian P, Mansour kiaie. Antifungal activity of silver nanoparticles on some fungi. Int. J. Nano. Dim. 2011; 1 (3): 233- 239. Available from: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=1943 94

43. Klasen HJ. A historical review of the use of silver in the treatment of burns. Π. Renewed interest for silver. Burns. 2000; 26: 131-138. DOI: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00116-3

44. Russell AD, Hugo WB. 7 Antimicrobial activity and action of silver. Prog. Med. Chem. 1994; 31: 351- 70. DOI: 10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70024-9

45. Silver S. Bacterial silver resistance: Molecular biology and uses and misuses of silver compounds. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev. 2003; 27: 341- 353. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00047-0

46. Baker C, Pradhan A, Pakstis L, Pochan DJ, Shah SI. Synthesis and antibacterial properties of silver nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2005; 5: 244- 249. DOI: 10.1166/jnn.2005.034

47. Lee BU, Yun SH, Ji JH, Bae GN. Inactivation of S. epidermidis, B. subtilis, and E. coli bacteria bioaerosols deposited on a filter utilizing airborne silver nanoparticles. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008; 18: 176- 182. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18239437

48. Melaiye A, Sun Z, Hindi K, Milsted A, Ely D, Reneker DH, et al. Silver (I)-imidazole cyclophane gem-diol complexes encapsulated by electrospun tecophilic nanofibers: Formation of nanosilver particles and antimicrobial activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005; 127: 2285- 2291. DOI: 10.1021/ja040226s

49. Sondi I, Salopek SB. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agents: A case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. J. Colloid. Interface. Sci. 2004; 275: 177- 182. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2004.02.012

50. Jiang ZJ, Liu CY, Sun LW. Catalytic properties of silver nanoparticles supported on silica spheres. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005; 109 (5): 1730-5. 10.1021/jp046032g

51. Rajesh Kumar S, Malarkodi C, Venkat Kumar S. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from marine brown seaweed and its antifungal efficiency against clinical fungal pathogens. Asian. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017; 10 (2): 190-193. DOI: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i2.15127

52. Finegold SM, Baron EJ. “Bailey and Scotts Diagnostic Microbiology” 7th Ed., The C.V. Mosby Company, St. Louis. 1986.

53. NCCLS. Method for Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Guideline. NCCLS document M44-A [ISBN 1-56238-532-1]. NCCLS, 940 West Valley Road, Suite 1400, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087-1898 USA, 2004.

54. Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, Senapati S, Sainkar SR., Khan MI. Fungus-mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their immobilization in the mycelial matrix: A novel biological approach to nanoparticle synthesis. Nano. Lett. 2001; 1 (10): 515- 519. DOI: 10.1021/nl0155274

55. Mukherjee P, Ahmad A, Mandal D, Senapati S, Sainkar SR., Khan MI, Kumar R. Extracellular synthesis of gold nanoparticles by the fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Chem. Biochem. 2002; 3 (5): 461- 463. DOI: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020503)3:5<461::AIDCBIC461>3.0.CO;2-X

56. Gonzalo J, Serna R, Sol J, Babonneau D, Afonso CN. Morphological and interaction effects on the surface plasmon resonance of metal nanoparticles. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2003; 15 (42): 3001-3002. Available from; https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0953- 8984/15/42/002/meta

57. Alt V, Bechert T, Steinruecke P, Wagener M, Seidel P, Dingeldein E, et al. An in vitro assessment of the antibacterial properties and cytotoxicity of nanoparticulate silver bone cement. Biomaterials. 2004; 25: 4383– 4391. DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.078

58. Shafaghat A. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles by the phytosynthesis method and their biological activity. Synth. React. Inorg. Metal–Org. Nano-Metal. Chem. 2015; 45: 381– 387. DOI: 10.1080/15533174.2013.819900

59. Kim J, Lee J, Kwon S, Jeong S. Preparation of biodegradable polymer/silver nanoparticles composite and its antibacterial efficacy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009a; 9: 1098- 1102. DOI: 10.1166/jnn.2009.c096

60. Ahmed RH, Mustafa DE. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by traditionally used medicinal plants in Sudan. Int. Nano. Lett. 2020; 10: 1–14. DOI: 10.1007/s40089-019-00291-9

61. Anupam R, Onur B, Sudip S, Amit KM, Yilmaz MD. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles: biomoleculenanoparticle organizations targeting antimicrobial activity. RSC. Adv. 2019; 9: 2673-2702. DOI: 10.1039/C8RA08982E

62. Anes As, Kasing A, Micky V, Devagi K, Lesley MB. Enhancement of antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram positive and gram negative using blue laser light. Intl. J. Photoene. 2019; 1-12. DOI: 10.1155/2019/2528490

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)