INTRODUCTION

The problems associated with mycotoxin contamination of grains are worldwide. Mycotoxic moulds generally attack the kernels of grain robbing the nutrients and lower the fat, protein and vitamin content of the grain. The mould also often changes the colour of the grains, the consistency/texture and often imparts an odour that causes feed refusal in animals. Aflatoxins are produced by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus in both field and storage. Infection is most common after the grains have been damaged by insects, birds, mites, hail, frost, heat and drought stress, windstorms and other unfavourable weather conditions (Jacobsen et al., 1993). Aflatoxins contamination can occur in a wide variety of feedstuffs including maize, sorghum, barley, rye, wheat, peanuts, soybean, rice, cottonseed and various derivative products made from these primary feedstuffs (Busby and Wogan, 1979). The formation of aflatoxins is influenced by physical, chemical and biological factors. The physical factors include temperature and moisture. The chemical factors include the composition of air and the nature of the substrate. Biological factors are those associated with the host species (Hesseltine, 1983). Aflatoxicosis have produced severe economic losses in the poultry industry affecting ducklings, broilers, layers, turkeys and quail (CAST, 1989). In poultry, aflatoxin impairs all important production parameters including weight gain, feed intake, feed conversion efficiency, pigmentation, processing yield, egg production and male and female reproductive performance. Some influences are direct effects of intoxication, while others are indirect, such as from reduced feed intake (Calnek et al., 1997). In order to produce aflatoxin for mycotoxin research, the present study was an attempt to establish the optimum aflatoxin production requirements by Aspergillus parasiticus under laboratory conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Lyophilized preparations of Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 was obtained from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Peoria (U.S.A.) and Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 was procured from the Institute of Microbial Technology (IMTECH), Chandigarh, India. These lyophilized preparations were revived on potato dextrose agar medium and used for experimentation. Fifty grams of cracked maize and broken rice were taken separately in 100 ml. conical flasks. The moisture content of each substrate was adjusted to obtain desired moisture levels of 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 per cent. The flasks were plugged with nonabsorbent cotton and sealed with aluminium foil. The flasks were autoclaved at 121°C for 20 minutes and inoculated with 10 days old spores of two strains of Aspergillus parasiticus (i.e. NRRL 2999 and MTCC 411 strains). The inoculated flasks were incubated in a Remi make BOD incubator for desired periods of 7, 14, 21 and 28 days each in duplicate. Thus, a total of 96 flasks (48 for maize and 48 for rice substrates) for each strain of Aspergillus parasiticus were used in this experiment. After removal from the incubator, the flasks were dried at 80°C and the aflatoxin production was estimated as per the method given by Pons et al (1966). The aflatoxin standard used in the present study was procured from M/s Sigma Co. (USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

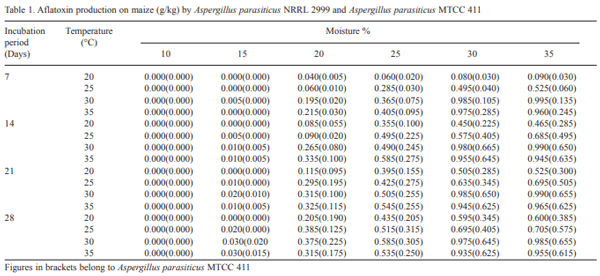

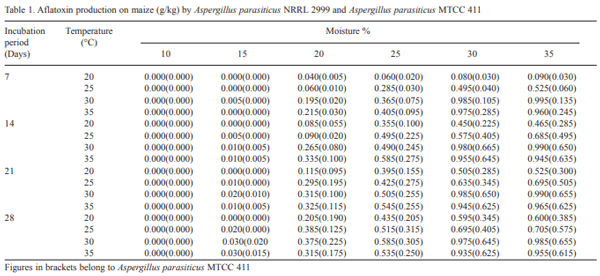

The effect of moisture, temperature and incubation periods on aflatoxin production on cracked maize by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 and Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 has been recorded in Table 1. Even after inoculation of cracked maize with aflatoxigenic fungi, neither Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 nor Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 could produce aflatoxin at 10 per cent moisture level at any temperature or incubation periods. Further no aflatoxin production was detected at 20°C temperature and at 15 per cent moisture level in any of the incubation periods either by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 or Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 strain. This indicated the importance of temperature and moisture content of the substrate in aflatoxin production. Hesseltine (1983) also reported that temperature and moisture content of the substrates are the two important physical factors that influence the formation of aflatoxin. The Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 started aflatoxin production at 15 per cent moisture and 30°C temperature in 7 days of incubation period, whereas, in the case of Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411, aflatoxin production was also recorded at 15 per cent moisture and 30°C temperature but in 14 days of incubation period. This suggested that the requirements of moisture and temperature to start aflatoxin formation are similar for both the strains but Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 took longer period of incubation as compared to Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 strain.

The highest production of aflatoxin (0.995 g/Kg maize) by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 was recorded at 35 per cent moisture and 30°C temperature in 7 days of incubation period, whereas, in case of Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411, maximum aflatoxin production (0.665 g/Kg maize) was recorded at 30 per cent moisture and 30p C temperature in 14 days of incubation period. During 7 days of incubation period and up to 30°C temperature, the aflatoxin production by both the strains of fungi, increased with the increase in moisture content upto 35 per cent. Thus, both the strains produced maximum aflatoxin at 30°C temperatures, however, the requirement of incubation periods was different. Therefore, maximum yield of aflatoxin can be harvested on 7 days of incubation for Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 and on 14 days of incubation period for Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411. Considerably higher yield of aflatoxin was obtained between 30 and 35 per cent moisture levels and from 30 to 35°C temperature. Lillehoj (1983) reported that the limiting temperatures for the production of aflatoxin by Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus are 12 to 41°C, with optimum production occurring between 25 and 32°C. Royes and Yanong (2002) also suggested that the synthesis of aflatoxin in feeds are increased at temperature above 27°C and moisture level in the feed above 14 per cent.

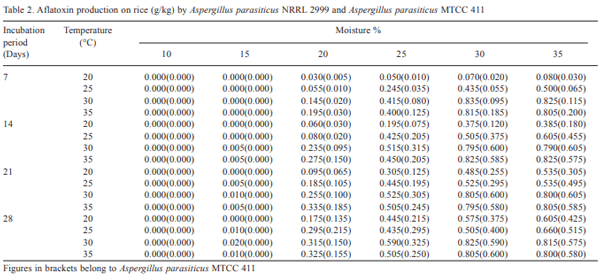

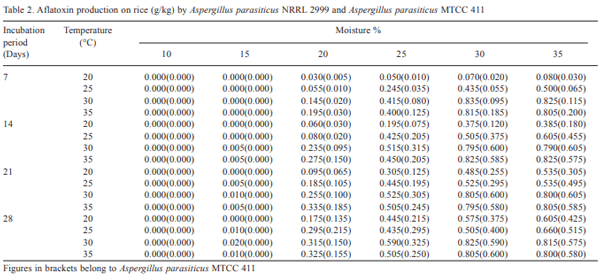

Aflatoxin production on broken rice by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 and Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 at different moisture, temperature and incubation periods has been recorded in Table 2. As in the case of maize, no aflatoxin was detected at 10 per cent moisture level and at any temperature or incubation periods either by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 or Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411. Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 started producing aflatoxin at 15 per cent moisture and 30°C temperature in 14 days of incubation period, whereas, Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 did not produce aflatoxin at 15 per cent moisture and at any temperature or incubation periods. Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 started aflatoxin formation at 20 per cent moisture level in 7 days of incubation period and at 20°C temperature.

The maximum production of aflatoxin (0.835g/Kg rice) by Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 was recorded at 30 percent moisture and 30°C temperature on 7 days of incubation period, however, in case of Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411, maximum yield of aflatoxin (0.605g/ Kg rice) was recorded at 35 percent moisture and 30°C temperature on 14 days of incubation period. Shotwell et al. (1966) also developed a method for the production of aflatoxin by Aspergillus flavus on rice substrate. They concluded that the peak yields of aflatoxins (1.511g/Kg rice) were obtained in 5 days of incubation at 28°C temperature. Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 produced more amount of aflatoxin as compared to Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411, however, the aflatoxin yield on maize was higher as compared to rice suggesting that maize is a better substrate for aflatoxin production.

It is inferred from the study that the aflatoxigenecity of Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 is higher as compared to Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411 and the maximum yield of aflatoxin is obtained between 30 and 35 per cent moisture and at 30°C temperature on 7 days of incubation for Aspergillus parasiticus NRRL 2999 and 14 days of incubation for Aspergillus parasiticus MTCC 411.

This article was originally published in Indian Journal of Poultry Science (2012) 47(1): 75-78.